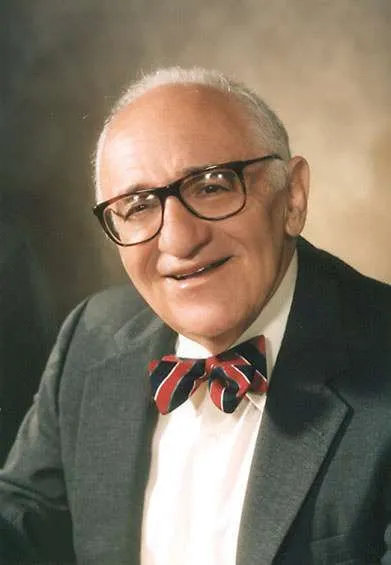

Dr. Rothbard is a professor of economics at the Polytechnic Institute of

The lone individual is seldom given credit as a shaper and mover of great historical events; and this is particularly true when that individual is no famous statesman or military hero, nor leader of a mass movement, but simply a little-known person pursuing his own idea in his own way. Yet such a person, scarcely known in his day and totally forgotten by historians until the last few years, played an important role in one of the most significant events in modern history: the American Revolution. In all the welter of writing on the economic, social, political, and military factors in the Revolution, the role of this one obscure man, who directed no great events nor even wrote an influential book, had been completely forgotten; and yet now we know the great influence of this man and his simple idea in forming an event that has shaped all of our lives.

Thomas Hollis of

His Own Kind of Public Service

Offered a chance, in his mid-thirties, to enter Parliament, Hollis refused to join what he considered the inevitable corruption of the political life; instead he decided to devote himself to his Plan to distribute libertarian books. Hollis thus came to spend the bulk of his life collecting and disseminating books and pamphlets and mementoes of liberty where he believed they would do the most good; when books could not be obtained, he financed the republishing of them himself. Every phase of their publication and distribution was shepherded through by Hollis as a labor of love. The typography, the condition of the prints, the luxurious binding and stamping, all were enhanced by his efforts. When sending a book as a gift to a library, person, or institution, which he usually did anonymously, Hollis took the trouble to inscribe the title page with mottoes and quotations appropriate to the book itself. Even “liberty coins,” medals, and prints were collected by Hollis and sent to where they might best be used.

At first, Thomas Hollis sent the benefits of his largesse far and wide, throughout Europe and Asia as well as

Hollis supplemented these activities by sparing no effort on behalf of the American colonists, including writing letters, public and private, wherever he could and reprinting and distributing writings favorable to the Americans. These works included tracts by American and English authors, as well as letters by Hollis’ friends written to the

Samuel Johnson Pays Tribute

While far from famous in his own day, Thomas Hollis and his Plan were well known in English intellectual circles, where that crusty old Tory, Dr. Samuel Johnson, angrily pinned upon Hollis the responsibility for the American Revolution. Ironically, Johnson had at first brusquely dismissed the unprepossessing Hollis as a harmless “dull poor creature.” Professor Caroline Robbins, who has done yeoman work in rescuing Hollis from total obscurity, eloquently concludes that Dr. Johnson’s final assessment was not so very wrong:

When his gifts to Americans of his “liberty books” and his propaganda for them are considered, Dr. Johnson’s attribution to Hollis of some share at least in the American Revolution seems hardly exaggerated. . . .

The famous plan of Thomas Hollis of

Lincoln ‘sInn was itself a microcosm of the activities of all his liberal contemporaries. Those books, pictures, medals, and manuscripts he began to collect as a young man in the reign of George II represented to him and to his friends the great tradition of English liberty. He wanted to spread knowledge of this sacred canon around the world. As he saw in the policies of George III and his ministers a threat to all he most valued in his dear, native land, he concentrated his efforts to send overseas American friends as much of the heritage as could be confined in print and portrait. TheNew World would provide an asylum for the freedom his ancestors had fought for in the old.

Hollis was right. In

America the academic ideas of the Whigs of theBritish Isles were fruitful and found practical expression. Americans opposing English policies made claims which could be contradicted from past experience and practice, but in using the natural rights doctrines they were appealing to tradition still lively among their English sympathizers. . . .1

Thomas Hollis’ most direct influence in

Thomas Hollis was not destined to see the fruit of his beloved Plan in the American Revolution. But though this lone man of learning was quickly forgotten, recent historians, in the wake of the researches of Caroline Robbins, have begun to recognize the tremendous influence upon the American Revolution, not only of Hollis himself, but of the entire English libertarian tradition which Hollis did so much to revive and disseminate. The recent works of Charles W. Akers, David L. Jacobson, and particularly Bernard Bailyn have demonstrated how much the birth of

Footnotes

1 Caroline Robbins, The Eighteenth-Century Commonwealthman (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1959), pp. 268, 384-85. Miss Robbins first resurrected the role of Hollis in her “The Strenuous Whig, Thomas Hollis of