Development needs institutional reform.

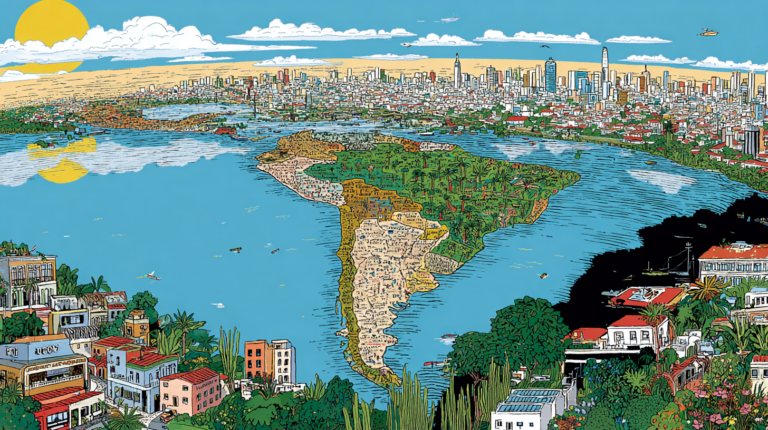

The persistence of underdevelopment in Latin America cannot fully be explained solely by external factors, colonial legacies, or unfavorable cycles in the international economy. While these elements have played a significant role throughout history, it has become increasingly evident that the main obstacles to the region’s sustainable development lie in the fragility, capture, and dysfunctionality of its institutions. If the countries of this region intend to break with its history of low growth, inequality, and instability, the first step is to correct their political, legal, and economic institutions.

The literature on institutional economics, championed by authors such as Douglass North and, more recently, Nobel laureates Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson, demonstrates that long-term economic growth fundamentally depends on the existence of inclusive institutions. These are institutions capable of guaranteeing property rights, limiting the arbitrary exercise of power, ensuring normative predictability, and promoting competition. In contrast, extractive institutions concentrate power, distribute privileges to specific groups, and organize the economy around rent-seeking rather than value creation. Unfortunately, this second model still predominates in much of Latin America.

Venezuela represents the most extreme and tragic example. The construction of an authoritarian regime, marked by systematic violations of human rights, suppression of civil liberties, and the absence of alternation of power, transformed the Venezuelan state into an openly extractive structure. One of the most significant examples of the subversion of a productive chain into an extractive institutional structure was the statization of Venezuela’s main oil company, PDVSA, in 2006. This destroyed the company’s technical autonomy and international integration, while simultaneously converting it into a political instrument of the regime, replacing technical criteria with ideological loyalty, using oil revenue for clientelist financing, and directly transferring resources to power networks associated with the government. The result of the crisis in the institution was a productive crisis, where since 2008 the company has been decreasing its production, which had always been the main asset of the Venezuelan economy.

International isolation and tax embargoes against the regime, a direct consequence of its blatant break with minimum democratic standards revealed in the 2024 electoral fraud, have driven away investments, financially reduced the country’s productive capacity, and pushed the economy toward a kind of corporatism and schemes of political favoritism. In this environment, only groups aligned with the dictatorship are able to prosper, while the population faces widespread impoverishment, mass exodus, and institutional collapse. The Venezuelan experience unequivocally illustrates how the destruction of institutions preceded and deepened economic destruction.

In Colombia, institutional fragility manifests itself less through formal ruptures and more through the persistence of structures parallel to power that challenge the authority of the State. The legacy of armed conflict, the historical actions of the FARC, left-wing guerrilla forces originally formed during the Cold War, and the incomplete dismantling of illegal groups have resulted in a country where organized crime still exerts effective control over entire regions, imposing its own rules alongside those of the State. The Gulf Clan symbolizes this territorial capture, highlighting the institutional incapacity to guarantee security, property rights, and economic freedom. Instead of confronting this structural problem, the government has prioritized an agenda of political populism, relativizing the role of formal institutions and the enforcement of laws. This is reflected in measures such as the 2024 pension reform, which included a reduction in the contribution period, a global counter-trend, and abrupt increases in the minimum wage, which grew by almost a quarter in 2025. Although presented as social policies, these decisions increase informality, deteriorate fiscal sustainability, and remove investments, reinforcing the cycle of populism and institutionalized fragility.

The Brazilian case reveals a more complex and ambiguous picture. Brazil maintains competitive elections, a free press, and functioning formal institutions. The Judiciary, in particular, has played a relevant role in containing attacks on the constitutional order and protecting against recent attempts at democratic rupture. This leading role was essential for the preservation of the democratic regime. However, from this legitimate role, a worrying movement of continuous expansion of powers is observed, with increasing interference in matters typical of the other branches of government. The country suffers severely from the excessive judicialization of politics; regulatory insecurity and the accumulation of prerogatives and privileges have transformed the Brazilian Judiciary into the most expensive in the world in terms of proportion to the public budget, without this necessarily translating into greater efficiency or predictability. This demonstrates the structural bottleneck and the extractive character of the institution, and also brings the risk of replacing one institutional problem with another: the defense of democracy cannot serve as a pretext for the erosion of institutional limits and the accumulation of privileges.

Argentina, in turn, offers an interesting case of transition, but one that remains incomplete. After decades marked by economic populism, chronic inflation, and institutional instability, the country seems to be beginning a still incipient and politically costly movement to confront clearly extractive structures. Reforms aimed at fiscal discipline, rationalization of the state, and reduction of economic distortions indicate a war of institutional reconstruction. However, significant obstacles persist, among them the historically dominant role of trade unions. Argentina is among the most unionized countries in the world, with unions wielding disproportionate economic and political influence, often operating according to a logic of blockade, coercion, and exclusion of income. Instead of acting as legitimate mediators of labor relations, these unions frequently function as extortion structures, hindering investment, innovation, and the creation of formal jobs. Whether Argentina will be able to reform its institutions permanently remains to be seen, but it seems clear that overcoming this model will be crucial to the success of the Argentine experience.

These national examples, despite their differences, converge on the same conclusion: Latin America suffers less from a lack of resources and more from an excess of extractive institutions. States captured by corporations, corporatist political elites, unions, or armed groups fail to provide the legal security and predictability necessary for development. The result is a recurring pattern of interrupted growth, commodity dependence, and vulnerability to external shocks.

Overcoming this situation requires more than just one-off economic reforms. It demands a regional commitment to institutional protection, based on clear limits to power, respect for democratic rules, and strengthening the rule of law. Institutions must be instruments of social cooperation, not permanent arenas of conflict or mechanisms for distributing privileges. Without this transformation, any development strategy will be doomed to produce only temporary results.

International experience demonstrates that countries that have succeeded in breaking the cycle of underdevelopment have done so, above all, through the consolidation of inclusive institutions. For Latin America, this lesson is particularly urgent. Economic growth does not precede institutions, but rather depends on them. As long as the region does not face this challenge directly and honestly, it will remain trapped in a past that insists on repeating itself.