A review of Gary Galles’s ‘Freedom in One Lesson: The Best of Leonard Read.’

This book review first appeared in the December 2025 issue of Quadrant.

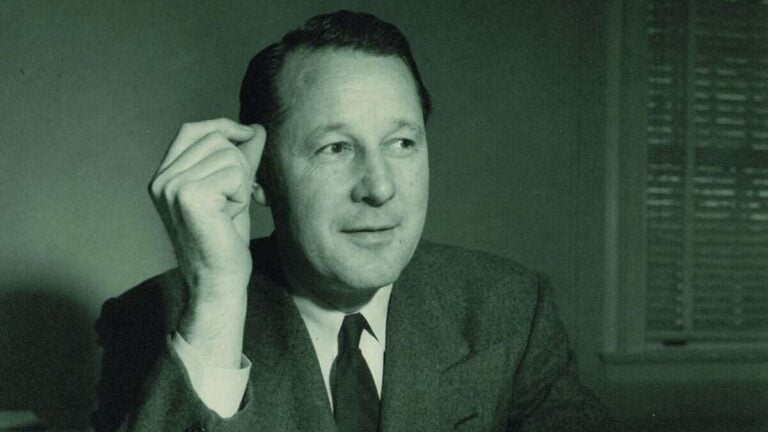

Two generations before Charlie Kirk there was Leonard Read. He too travelled the country debating with students and telling them how to build a good society.

The essence of Read’s philosophy comprises individual liberty, the free market, private property, and government limited to securing these rights equally for all. Everyone is free to do as they please provided they do not infringe on the equal right and opportunity of everyone else to do so too. Everyone can pursue their ambitions; associate with whomever they please; worship God in their own way; choose their own job or profession; run a business; and keep their honestly acquired property and savings or dispose of it as they wish. The society prospers because it uses the creative talents and resources of all its citizens, not just an elite few.

In Freedom in One Lesson, Gary Galles curates Read’s books, speeches and essays, and shows their contemporary relevance. The title pays homage to Read’s friend and colleague Henry Hazlitt, who in 1946 wrote Economics in One Lesson, a book still unmatched for teaching the principles of sound economics. That same year, Read and Hazlitt formed the Foundation for Economic Education (FEE) dedicated to inspiring, educating, and connecting future leaders with the economic, ethical, and legal principles of a free society. Nearly eighty years later, the FEE continues its mission—through online courses, essays, seminars, conferences and scholarships.

Read is most famous for his brilliant essay “I, Pencil.” In telling the life story of a simple pencil, he demonstrates how the price miracle facilitates the economic collaboration of millions of people. In worldwide supply chains they produce myriads of things. Everyone prospers by doing their bit without needing to know what the others are doing. There is no mastermind, no one controlling their activities. The “miner of graphite in Ceylon and the logger in Oregon” have no idea they are contributing to the manufacture of a pencil.

Perhaps the most telling consequence of Read’s philosophy is that it leads to a more moral society. The zeitgeist of his time was that the communism of Stalin and the socialism of Roosevelt’s New Deal created societies of equality. In practice it did not work out that way. The horrors of communism have been well documented, but the errors of the social-democratic welfare state are not so obvious.

The morality of the latter is based on compassion for victims. The welfare state compulsorily acquires from those who have—regardless of how honestly it has been acquired—and redistributes it to those who have not—regardless of the cause of their disadvantage. The unintended consequence is that less work is done by the capable, fewer risks are taken by the entrepreneurs, and the number of citizens entitled to benefits grows. Individual responsibility declines. Crime flourishes. The decline in prosperity means there is less wealth to share than there might have been. Moreover, the benefits do not flow primarily to the poor and the disadvantaged, they flow to a new class of political bureaucrats, academics, and crony capitalists. Milovan Djilas documented this in his 1957 classic The New Class, where he analysed the communist system of the Soviet Union and his native Yugoslavia. Today, Djilas’s themes are repeated in Brussels, Washington and Canberra.

Nowadays, we take it for granted that our politicians will enhance their prospects of being re-elected by doing special favours for those in their electorates, or for those who fund their party. Also, that they will enlist public servants to promote them on social media and employ consultants at public expense to write reports to support their ideologically driven projects.

In contrast, Read believed that:

A good government… cannot be a government that divides the population into classes… A good government is one whose administrators must think of themselves only as representatives, as servants of the people, administering just laws, impartially and impersonally. They must never assume the notion that election or appointment to office places them in positions from where an undelegated, arbitrary attitude is permissible. They must never think, the minute they are in office, that they are members of a new class, a different interest, that they must fortify their new positions by intrigues and favours to assure their permanency.

Just as Charlie Kirk did when he engaged in debate with university students, Leonard Read was a practitioner of Socratic dialogue. In the following excerpt, Read argues that it cannot be right for a government to do something that we would regard as morally wrong if done by an individual.

Q: Joe Doakes was lynched. Who did it?

A: A mob.

Q: A mob is but a label. Of what is it composed?

A: Individuals.

Q: Then did not each individual in the mob lynch Joe Doakes?

A: That would seem to be the case.

Q: Very well. Can any individual gain absolution by committing murder in the name of a label, the mob, a collective?

A: I guess not.

Q: Now that we have established that point, let me pose another question. Do you believe in thievery?

A: Of course not.

Q: Logically, then, you do not believe that you should use force to take my income to feather your own nest. True or false?

A: True.

Q: Is the principle changed if two of you gang up on me?

A: Not at all.

Q: One million? Even a majority?

A: Well perhaps OK if a majority does it.

Q: Do you mean that makes it right?

A: Oh, no.

Q: That is what you have just said. Would you care to retract that?

A: To be logical, I must.

Q: You have now agreed that not even 200 million people or any agency thereof: government, labor unions, educational institutions, business firms, or whatever—have a moral right to feather their nests at the expense of others, that is, to advance their own special interests at taxpayers’ expense. You have also admitted that no one gains absolution by acting in the name of a collective. Therefore, is not every member who supports or even condones a wrong collective action just as guilty as if he personally committed the act?

A: I have never thought of it that way, but now I believe you are right.

Freedom in One Lesson is a fine contribution to our debate on how to improve our society so that everyone can live happy, prosperous and meaningful lives. We are indebted to Gary Galles for rejuvenating the work of Leonard Read and explaining its relevance to contemporary issues. Read’s influence, and the continuing work of the FEE, is a nice complement to Turning Point USA and the legacy of Charlie Kirk.