National holidays have edged out local celebrations.

It’s November 25. If you’d been living in New York more than a century ago, you might have known this day as a holiday. Commemorating the end of the War of Independence, it marked the day British forces evacuated New York City, following the formal cessation of the conflict with the Treaty of Paris in 1783. After the British troops left, George Washington led the triumphant Continental Army through the city from north to south. Evacuation Day, as it came to be known, was celebrated annually with fancy dinners and events through the 19th century. There were fireworks, parades, and children had a holiday from school.

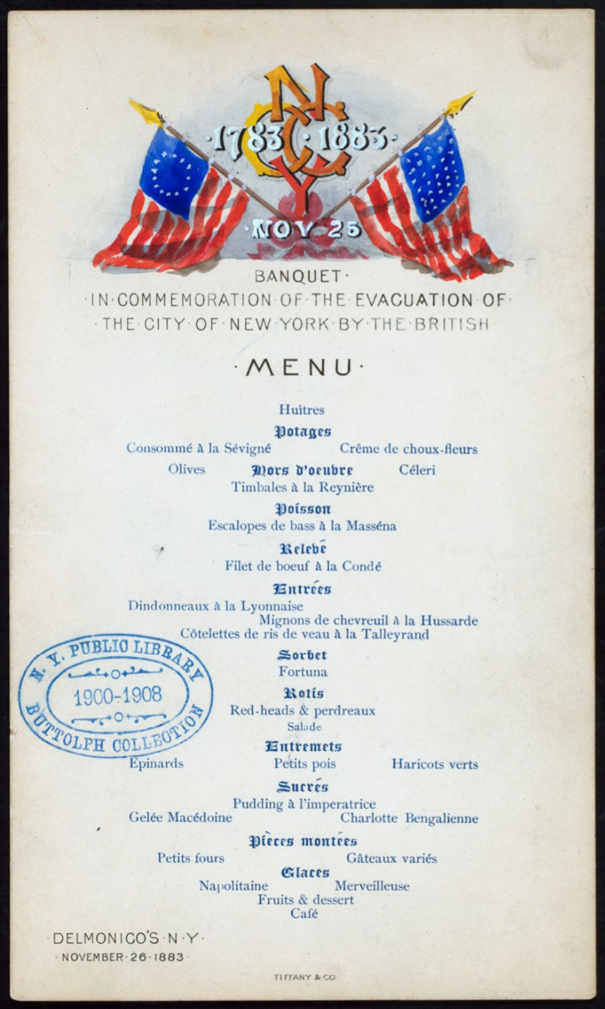

The New York Public Library holds a menu from a banquet held at Delmonico’s in 1883, for the centennial of the evacuation. Diners celebrated with courses of fish, beef and turkey, pheasant, and multiple desserts.

As we look towards America’s 250th next year, it’s worth reflecting on the ways in which the events of 1776 and the Revolutionary War were remembered over the decades to follow. Note, for instance, that the Fourth of July did not become a federal holiday until 1870—long after the passing of anyone who remembered the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

But in that interval, plenty of local commemorations had sprung up, and many places in the country had their own holidays and celebrations to mark events in the war. Remembrance was local and specific, marking a direct community connection to the war, until mass communication made the commemoration events more national and shared.

Massachusetts, unsurprisingly, was quick to mark the significance of revolutionary events. Patriots’ Day, April 19, marks the first battles of the war, at Lexington and Concord in 1775. This day is, perhaps more surprisingly, celebrated in 7 other states, including North Dakota and Utah (who signed on to recognize it just this year).

Massachusetts also got the jump on recognizing the Fourth of July, declaring it a day of public rejoicing in 1781. The Bay State even has its own Evacuation Day, observed in Suffolk and Somerville Counties, marking the departure of British forces after the Siege of Boston. Perhaps unfortunately, it takes place on March 17—more familiar to most Bostonians as St. Patrick’s Day.

Not wanting to be left out, Vermonters celebrate Bennington Battle Day on August 16, commemorating the American victory at the Battle of Bennington. Which took place in New York.

South Carolinians celebrate Carolina Day, which marks the victory of American forces in the Battle of Sullivan’s Island, on June 28, 1776, where defending troops successfully held off a British naval attack.

In all these places we see people were keen to remember, and celebrate, events local to them—where at least in the early years, living witnesses were part of the festivities. Boosts to such celebrations came in 1824–25 with the tour of the Marquis de Lafayette.

Having served with the patriots during the war, he returned 50 years later to much fanfare. The last surviving Major General of the war, he was a living link to the past, and local committees were falling over themselves to host him and celebrate. He visited every state, making his way by carriage and steamboat, greeted by cheering crowds—and many elderly veterans. This tour created its own culture of commemoration, as towns marked “Lafayette Day” in the years to come, remembering his visit.

The Sesquicentennial in 1926 brought another burst of remembering, with reenactments, plaques—and a craze for colonial revival architecture. But local festivities were already dropping off calendars.

As for Evacuation Day in New York, its decline in significance was noted by the start of the 20th century, and it would disappear from city schedules soon after. According to Megan Margino of the New York Public Library: “The United States’ alliance with Britain in World War I seemed to provide the final push in ceasing celebrations altogether, and the last official Evacuation Day was seen in 1916—commemorated by 60 veterans and a ceremonial flag raising at the Battery.”

Now, people across the country will celebrate the Fourth of July, but not a local holiday that relates specifically to what may have happened right near to them. The War of Independence has become a national narrative, and an inclusive one. Generations of immigrants grew to see themselves in the War of Independence. To celebrate it is to be American, but not a New Yorker or a Bostonian. The collective remembering has come at a trade-off of local forgetting.