Can you find the disappearing labor force?

At one time or another, we have all been intrigued by graphic puzzles that invite us to find Waldo, the proverbial everyman lost in a photo packed with people. A creation of Martin Handford, a British writer of children’s stories, Waldo is fun to find in the crowd for young and old alike. But Handford offers puzzles that can be solved. Look long enough and Waldo will surface.

Would that the search for the U.S. labor force in these times were as easy.

The share of the U.S. working-age population employed or seeking jobs, which is called the civilian labor force participation rate, is at a 34-year low. In July 2013, the rate stood at 63.4 percent. In January 2008, when the last recession began, the number was 66.2 percent. The difference in just those two numbers accounts for a loss of 6.3 million workers. We have to go back to May 1979 to find anything lower than the current participation rate.

What on earth is going on? And why does it matter?

Writing about all this in The Atlantic in 2012, Derek Thompson bemoaned the situation: “We are at a modern historical low for working-age adults who are actually working, or trying to find work. It's horrible news. It means we make less stuff, have less wealth, and pay fewer taxes. It's bad for growth, bad for deficits, bad for the stock market.”

But is it good for people who are doing the best they can? Isn’t that the relevant question in a free society? What if the people making drop-out decisions are relying on those left working to help them along . . . without any prior agreement? Doesn’t that change things?

The decision to work or not is based mainly on incentives. When jobs open up and wages rise, people lay down their fishing poles and head to work. If unemployment compensation is extended, then some workers will wait a bit longer for something better before taking a low-paying job. If low-cost student loans are available, and may even be forgiven, then young people will opt for college, especially in hard times when there are no wages to lose by doing so. If not working is made more attractive than working, the law of supply says we will get more of it.

Yes, surely the problem is partly an economy that just doesn’t produce employment opportunities. But the American welfare state did not emerge from the 2008 recession.

As usual, there is more to the story. Let’s see if we can find those 6.3 million missing from the U.S. labor force.

Out-of-Work Carpenters?

A quick glance at the next chart suggests that about two million of the missing workers may be associated with lost jobs in the construction industry. Yes, it is possible for employment losses in one sector to be offset by gains in other sectors for the same workers, but perfect substitution just doesn’t work too well for specialized construction craft workers.

What About College Students?

The next chart shows the share of the population age 18–24 enrolled in post-secondary education. Notice how enrollment skyrocketed after 2007: About 2.4 million more kids have enrolled. Keep in mind that this is just the younger part of the enrolled population. There are also a lot of the over-24 group going to classes.

It only makes sense. Foregone wages make up the largest part of the cost of going to college. And if there is no work available, that part falls to zero. Add to this the availability of generous student loans subsidized by dear old Uncle Sam—you and me, my friend—and the industry booms. In academic year 2007–2008, total loans and federal grants to college students stood at $105.8 million in 2011 dollars. By 2011–2012, the total was $173.7 million, and rising. These figures make higher education look a lot like a growth industry to me, at least until the day of reckoning arrives.

If we take this 2.4 million into account, that leaves about two million more displaced job-seekers to account for.

Disabled Workers?

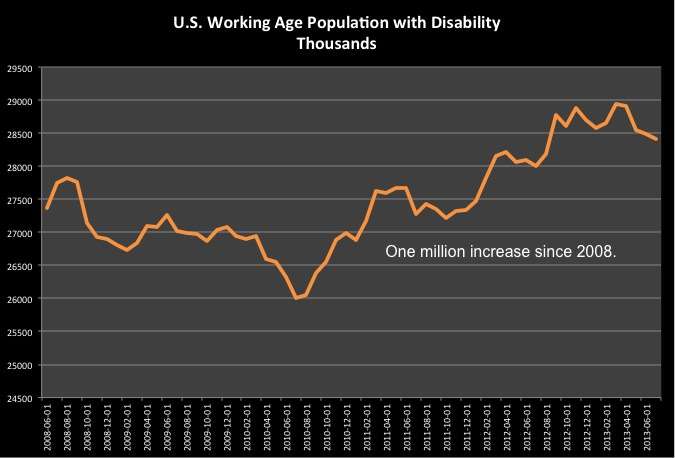

Let’s look at the count of people on disability. Since 2008, there has been an increase of one million in the number of work-age Americans receiving disability payments from the Social Security fund.

This leaves one million nonworking Waldos unaccounted for. Finding that group may not be as easy as the first few million.

Budding Entrepreneurs?

But there is another important group to consider. These are folks who may have started small businesses after losing their regular jobs, or while keeping their jobs. While they are technically still participating in the labor force, I am guessing that when labor market surveys are taken, the data for this group become rather blurred. Why would I say that?

Consider the Kauffman Entrepreneurship Index. This number is generated based on a large-sample survey that estimates the number of people out of 100,000 who started a business in the year of the survey. The next chart gives the results. First, notice how the number shot skyward as the recession became more severe. And notice how the number recedes as the recession goes away. The data illustrate the old saying, “When the going gets tough, the tough get going.”

Keep in mind that some, if not all, of these workers will be accounted for in the monthly employment survey that seeks to determine who is working, wishing to work, or no longer looking. But it is my guess that a lot of these entrepreneurs are missed in the count. We have gotten close to the 8.3 million workers who are no longer participating in the labor force.

Will Waldo Work Again?

Will Waldo go to work? And what will it take? The most recent reading on second-quarter 2013 real GDP growth came in at an annual rate of 2.5 percent, better than it has been but not enough to generate lots of job openings. There’s a good chance we will see 3.0 percent growth in 2014, if some of the Waldos return. Meanwhile, because of fringe benefit costs, labor is becoming more costly. Robots are getting cheaper. But as things slowly improve, some of the entrepreneurs will decide they are better off being on someone else’s payroll and will return to the traditional labor force. Others will not. The small business sector will prosper.

When the economy begins to hum, some of the disabled will decide their fortunes are better served by getting back to work; but many will not. The Social Security disability fund will be challenged to stay afloat. With a fired-up economy and a meaningful opportunity cost for going to school, a large number of students will head to work, perhaps hoping that someone else will pay off their student loans. And when construction gets on its feet again, a lot of construction workers will gladly get back to work, after having given up looking.

Yes, free people make decisions based on opportunities and incentives. In this sense, the low labor market participation rate makes sense. If we wish to be a part of a higher employment society, then we have to be willing to change some of the incentives cherished by the welfare state. Sometimes the threat of bankruptcy causes us to take some pretty tough actions.

Now is the time to change things.