Data show the benefits are far from certain.

The 2024 Olympic Games in Paris recently ended. With this event comes a typical avalanche of claims that the Games will produce a positive economic impact. One headline from Reuters claims that the Paris Games are expected to “buoy economic growth” for France in 2024.

Ata Ufuk Şeker, writing for Anadolu Ajansı, chronicles some of the estimates of the impact of the Olympic Games in France. He writes:

The official budget of Paris 2024 Olympics is estimated at $9.5 billion, and the hosting country’s expenditures for the duration of the event [are] estimated to reach $10.8 billion.

The Games are expected to contribute around $7.2 billion to $12 billion to the Paris Region, data from the French-based research organization Center for Law and Economics of Sport (CDES) showed.

The event will create 181,000 jobs and act as a lever to boost economic activity and employment, according to the Paris 2024 Organizing Committee for the Olympic and Paralympic Games.

A study conducted by the consultancy firm Asteres revealed that the spending associated with the organization of the Olympics is equivalent to public spending, as the study estimated that France will generate $5.7 billion in tax and social security revenues from the event.

This sounds like good news for France, but we should be wary of taking these statistics at face value. Historically, the Olympics has not been as financially kind to countries as initial estimates predicted.

Let’s look at some of the data to back up this claim. In their textbook The Economics of Sports, Michael A. Leeds, Peter von Allmen, and Victor A. Matheson survey available research to find estimates of the economic impact of the Olympic Games and other “mega-events” (e.g., World Cups and Super Bowls) before and after the event is held. The data show that these events often underperform expectations.

For example, the 2006 World Cup in Germany was estimated to add 60,000 new jobs, but on net it generated zero. The 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta was supposed to generate 5.1 billion dollars of impact, but had “no impact on taxable sales, hotel occupancy, or airport usage” according to Leeds, Allmen, and Matheson’s survey.

On the flip side, spending on the Olympics by host countries often exceeds expectations. Leeds, von Allmen, and Matheson document that the London 2012 Games bid was at $2.4 billion for direct expenses, but, when all was finished, the direct expenses were closer to $9 billion.

Mega Disappointments

Estimating economic impact is somewhat difficult, so not every mega-event has peer reviewed research to give us data, but the data above have a consistent theme: economic impact in terms of tax revenues, increased incomes, jobs, and tourism is consistently overstated by before-the-fact estimates. Economists who focus on sporting and mega-events pretty consistently agree that the true impact of these events is negligible at best.

Why do the estimates so often get things wrong? There are a few explanations for this which Leeds, von Allmen, and Matheson chronicle.

1) Substitution

The first issue with before-the-fact estimates is that they often fail to take into account substitutionary activities. For example, local Olympic attendees will often spend money that they would have otherwise spent elsewhere. This classic observation is based in the logic of Bastiat’s parable of the broken window.

The parable highlights the example that if a shopkeeper’s window is broken, we may be tempted to see the following silver lining: the shopkeeper will hire the glazier to make a new window; this income increase for the glazier will lead to him spending and employing others; and as a result, there will be higher incomes and more employment throughout the shopkeeper’s town.

Sounds good—so good we might be tempted to go around breaking windows. But put down your rocks.

The shopkeeper, in paying the glazier, no longer has money to spend on something else he may have wanted (e.g., a new suit from the tailor). Even if the shopkeeper kept the money in a bank, it could have been lent out for a long-term investment. The point is, we can easily see more income going to the glazier, but we miss the income which did not go to the tailor. Broken windows don’t generate wealth. Broken windows destroy wealth and move it around in visible ways.

The same is true with the Olympics. French attendees may spend money, but they would have spent that money elsewhere.

The authors also highlight that this might even be an issue with foreign guests. Imagine Mary, an avid sporting fan, always had a dream of going to Paris. In 2024, the stars align. She has the chance to fulfill her dream of going to Paris while she watches the Olympics. In this case, the Olympics didn’t generate additional revenue. Mary was always going to fulfill her Paris dream. The Olympics merely brings her spending at a particular time.

2) Crowding Out

The second reason revenue and jobs forecasts fall short is that they often don’t appreciate “crowding out.” Crowding is generally an economic bad. Other things equal, people would prefer that their favorite events and places were less crowded. Mega-events draw crowds, and the negative effects of crowds often cause locals and non-event tourists to stay in in order to avoid those crowds.

The 2002 Winter Olympic Games in Salt Lake City had an estimated $97 million impact on incomes. Not all sectors were affected equally, though. Hotels and restaurants in the area had a $70 million increase in sales. The problem is, this was offset by a $167 million decrease for general retailers. This makes sense when you understand crowding out. Tourist-heavy industries receive a lot more attention when tourists are in town, but, if the locals stay home, non-tourism-sensitive retailers will tend to suffer.

3) Bias in Estimating

At this point you may ask, “Why do these estimate-generators keep making these mistakes? Why not adjust the estimates way down to reflect the systemic overestimations of economic impact?”

It’s not possible to know for sure, but it’s clearly true that oftentimes the organizations which estimate economic impact want the mega-events to be successful. Politicians and external organizations stand to benefit from procuring mega-events. The claim that you helped the Olympics or the World Cup come to your city is a big résumé-booster for a mayor.

There are other interest groups which stand to gain from positive results. Is it any surprise that estimates generated by the NFL in 1999 far overestimated (relative to the historical estimates) the beneficial economic impact of hosting the Super Bowl?

Furthermore, insofar as particular industries benefit, we may expect them to be biased. For example, if economic impact estimators were trying to determine the benefit to the hospitality industry, would we expect the leaders in that industry to overestimate or underestimate the impact? The former seems more likely. Hotels are clear winners from mega-events, so insofar as estimates depend on the opinions of industry leaders, we would expect upward bias.

There’s nothing conspiratorial or diabolical in some deep sense being claimed here. It’s common in life for those who get very involved in a project or event to overestimate its positive significance.

However, we should also acknowledge that mega-events produce ample opportunity for corruption. The Olympic Games in Salt Lake City, for example, had their reputation tarnished by a bribery scandal. Similar scandals abound in mega-events (e.g., the 2022 World Cup). Insofar as event officials and city officials have the ability to access taxpayer dollars, concern for corruption is of high importance with mega events.

Counting the Cost

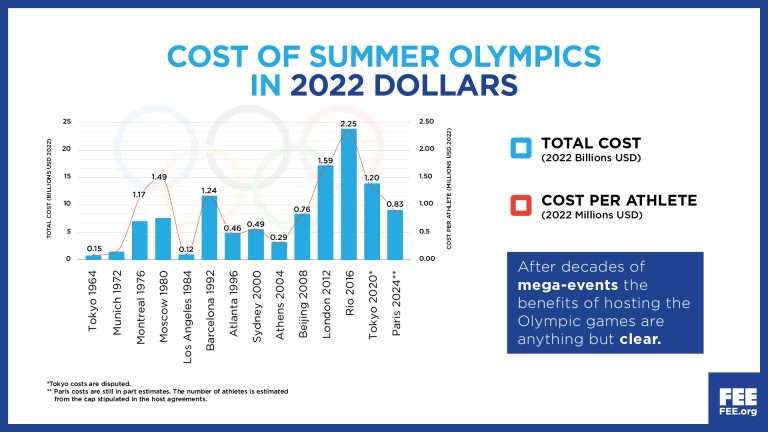

As mentioned before, the costs of the Olympics tend to be underestimated. But how much do they cost, and how much do they overrun the budgeted costs? Using data from a paper by Alexander Budzier and Bent Flyvbjerg, we can get a good breakdown.

On average the cost overrun is 159%, and it is typically worse for summer games than winter games.

So the benefits of hosting the Olympics, and mega-events more generally, tend to be overestimated, while the costs tend to be underestimated. Where does this leave us on net?

Well, in general, economic evidence is pretty clearly against the idea that the Olympics is generally a successful investment. Robert A. Baade and the aforementioned Victor A. Matheson authored a paper titled “Going for the Gold: The Economics of the Olympics” for the Journal of Economic Perspectives, in which they tracked the general economic impact of the Olympics.

In summarizing their results, the authors say, “[T]he overwhelming conclusion is that in most cases the Olympics are a money-losing proposition for host cities; they result in positive net benefits only under very specific and unusual circumstances” (p. 202).

So even in raw monetary terms, the Olympics tend to be a bum deal. But things are even worse than we might think. Think back to the parable of the broken window. Olympic infrastructure is built on the backs of taxpayers. To some extent, this loss to taxpayers can be counted. We know how much money was taken. But we do not know how much wealth (material or otherwise) taxpayers would have generated had they been allowed to keep their money. As with the shopkeeper, much of the cost to taxpayers in terms of lost opportunities remains unseen.

In summary, we should deny the broken-window logic that Olympic spending is some economic miracle.

If countries could grow rich from hosting the Olympics or other mega-events, then economic development would be easy. After decades of mega-events, however, it turns out the benefits are anything but clear.