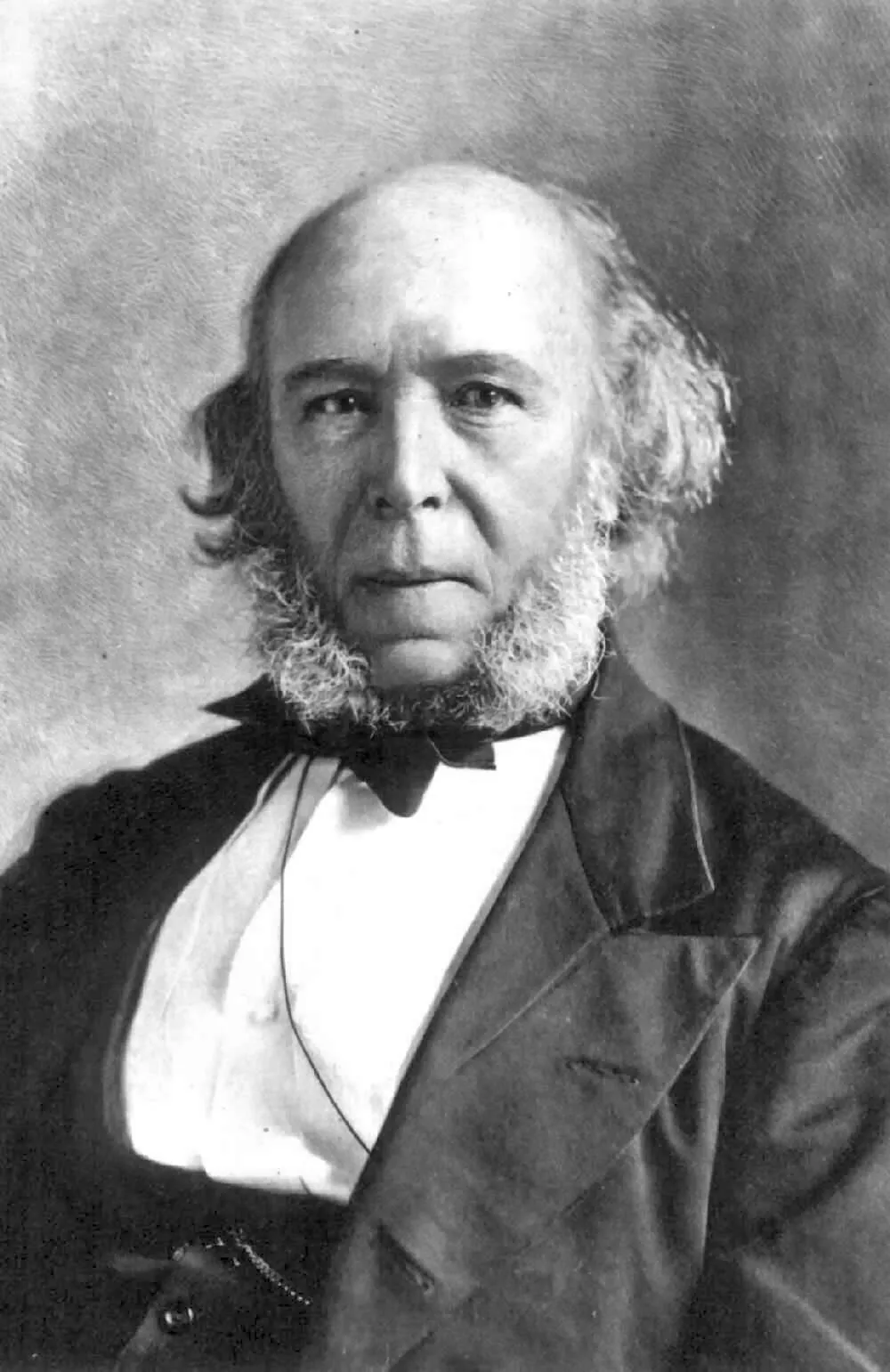

Editor’s note: To David Lawrence and his editorial in U. S. News and World Report of August 23, we are indebted for the reminder of Herbert Spencer’s classic presentation of the case for individual liberty.

The following excerpts are from the collection of Spencer’s essays, written during the latter nineteenth century and republished by Caxton Printers in 1940 as The Man Versus The State (213 pp. $3.50 cloth; also available from the Foundation for Economic Education, Inc., Irvington-on-Hudson, New York.)

It seems needful to remind everybody what Liberalism was in the past, that they may perceive its unlikeness to the so-called Liberalism of the present…. They do not remember that, in one or other way, all these truly Liberal changes diminished compulsory co-operation throughout social life and increased voluntary co-operation. They have forgotten that in one direction or other, they diminished the range of governmental authority, and increased the area within which each citizen may act unchecked. They have lost sight of the truth that in past times Liberalism habitually stood for individual freedom versus State-coercion.

And now comes the inquiry—How is it that Liberals have lost sight of this? How is it that Liberalism, getting more and more into power, has grown more and more coercive in its legislation? How is it that, either directly through its own majorities or indirectly through aid given in such cases to the majorities of its opponents, Liberalism has to an increasing extent adopted the policy of dictating the actions of citizens, and, by consequence, diminishing the range throughout which their actions remain free? How are we to explain this spreading confusion of thought which has led it, in pursuit of what appears to be public good, to invert the method by which in earlier days it achieved public good?

Unaccountable as at first sight this unconscious change of policy seems, we shall find that it has arisen quite naturally. Given the unanalytical thought ordinarily brought to bear on political matters, and, under existing conditions, nothing else was to be expected….

For what, in the popular apprehension and in the apprehension of those who effected them, were the changes made by Liberals in the past? They were abolitions of grievances suffered by the people, or by portions of them: this was the common trait they had which most impressed itself on men’s minds. They were mitigations of evils which had directly or indirectly been felt by large classes of citizens, as causes to misery or as hindrances to happiness. And since, in the minds of most, a rectified evil is equivalent to an achieved good, these measures came to be thought of as so many positive benefits; and the welfare of the many came to be conceived alike by Liberal statesmen and Liberal voters as the aim of Liberalism. Hence the confusion. The gaining of a popular good, being the external conspicuous trait common to Liberal measures in earlier days (then in each case gained by a relaxation of restraints), it has happened that popular good has come to be sought by Liberals, not as an end to be indirectly gained by relaxations of restraints, but as the end to be directly gained. And seeking to gain it directly, they have used methods intrinsically opposed to those originally used….

Things to Come

But we are far from forming an adequate conception if we look only at the compulsory legislation which has actually been established of late years. We must look also at that which is advocated, and which threatens to be far more sweeping in range and stringent in character. We have lately had a Cabinet Minister, one of the most advanced Liberals, so-called, who pooh-poohs the plans of the late Government for improving industrial dwellings as so much “tinkering”; and contends for effectual coercion to be exercised over owners of small houses, over landowners, and over ratepayers. Here is another Cabinet Minister who, addressing his constituents, speaks slightingly of the doings of philanthropic societies and religious bodies to help the poor, and says that “the whole of the people of this country ought to look upon this work as being their own work”: that is to say, some extensive Government measure is called for.

Again, we have a Radical member of Parliament who leads a large and powerful body, aiming with annually-increasing promise of success, to enforce sobriety by giving to local majorities powers to prevent freedom of exchange in respect of certain commodities. Regulation of the hours of labour for certain classes, which has been made more and more general by successive extensions of the Factories Acts, is likely now to be made still more general: a measure is to be proposed bringing the employees in all shops under such regulation.

There is a rising demand, too, that education shall be made gratis (i.e., tax-supported), for all. The payment of school-fees is beginning to be denounced as a wrong: the State must take the whole burden. Moreover, it is proposed by many that the State, regarded as an undoubtedly competent judge of what constitutes good education for the poor, shall undertake also to prescribe good education for the middle class—shall stamp the children of these, too, after a State pattern, concerning the goodness of which they have no more doubt than the Chinese had when they fixed theirs. Then there is the “endowment of research,” of late energetically urged. Already the Government gives every year the sum of £4,000 for this purpose, to be distributed through the Royal Society; and, in the absence of those who have strong motives for resisting the pressure of the interested, backed by those they easily persuade, it may by-and-by establish that paid “priesthood of science” long ago advocated by Sir David Brewster. Once more, plausible proposals are made that there should be organized a system of compulsory insurance, by which men during their early lives shall be forced to provide for the time when they will be incapacitated.

Nor does enumeration of these further measures of coercive rule, looming on us near at hand or in the distance, complete the account. Nothing more than cursory allusion has yet been made to that accompanying compulsion which takes the form of increased taxation, general and local. Partly for defraying the costs of carrying out these ever-multiplying sets of regulations, each of which requires an additional staff of officers, and partly to meet the outlay for new public institutions, such as board-schools, free libraries, public museums, baths and washhouses, recreation grounds, &c., &c., local rates are year after year increased; as the general taxation is increased by grants for education and to the departments of science and art, &c. Every one of these involves further coercion—restricts still more the freedom of the citizen. For the implied address accompanying every additional exaction is—”Hitherto you have been free to spend this portion of your earnings in any way which pleased you; hereafter you shall not be free so to spend it, but we will spend it for the general benefit.” Thus, either directly or indirectly, and in most cases both at once, the citizen is at each further stage in the growth of this compulsory legislation, deprived of some liberty which he previously had..

Impact on the Individual

In the first place, the real issue is whether the lives of citizens are more interfered with than they were; not the nature of the agency which interferes with them. Take a simpler case. A member of a trades’ union has joined others in establishing an organization of a purely representative character. By it he is compelled to strike if a majority so decide; he is forbidden to accept work save under the conditions they dictate; he is prevented from profiting by his superior ability or energy to the extent he might do were it not for their interdict. He cannot disobey without abandoning those pecuniary benefits of the organization for which he has subscribed, and bringing on himself the persecution, and perhaps violence, of his fellows. Is he any the less coerced because the body coercing him is one which he had an equal voice with the rest in forming?

In the second place, if it be objected that the analogy is faulty, since the governing body of a nation, to which, as protector of the national life and interests, all must submit under penalty of social disorganization, has a far higher authority over citizens than the government of any private organization can have over its members; then the reply is that, granting the difference, the answer made continues valid. If men use their liberty in such a way as to surrender their liberty, are they thereafter any the less slaves? If people by a plebiscite elect a man despot over them, do they remain free because the despotism was of their own making? Are the coercive edicts issued by him to be regarded as legitimate because they are the ultimate outcome of their own votes?…

This reply is, that these multitudinous restraining acts are not defensible on the ground that they proceed from a popularly-chosen body; for that the authority of a popularly-chosen body is no more to be regarded as an unlimited authority than the authority of a monarch; and that as true Liberalism in the past disputed the assumption of a monarch’s unlimited authority, so true Liberalism in the present will dispute the assumption of unlimited parliamentary authority….

Not the Form of Government, But the Restraints Imposed

The liberty which a citizen enjoys is to be measured, not by the nature of the governmental machinery he lives under, whether representative or other, but by the relative paucity of the restraints it imposes on him; and that, whether this machinery is or is not one he shared in making, its actions are not of the kind proper to Liberalism if they increase such restraints beyond those which are needful for preventing him from directly or indirectly aggressing on his fellows—needful, that is, for maintaining the liberties of his fellows against his invasions of them: restraints which are, therefore, to be distinguished as negatively coercive, not positively coercive….

Paper constitutions raise smiles on the faces of those who have observed their results; and paper social systems similarly affect those who have contemplated the available evidence. How little the men who wrought the French Revolution and were chiefly concerned in setting up the new governmental apparatus, dreamt that one of the early actions of this apparatus would be to behead them all! How little the men who drew up the American Declaration of Independence and framed the republic, anticipated that after some generations the legislature would lapse into the hands of wire-pullers; that its doings would turn upon the contests of office-seekers; that political action would be everywhere vitiated by the intrusion of a foreign element holding the balance between parties; that electors, instead of judging for themselves, would habitually be led to the polls in thousands by their “bosses”; and that respectable men would be driven out of public life by the insults and slanders of professional politicians….

The working of institutions is determined by men’s characters; and the existing defects in their characters will inevitably bring about the results above indicated. There is no adequate endowment of those sentiments required to prevent the growth of a despotic bureaucracy….

How Unselfish Are They?

But without occupying space with indirect proofs that the mass of men have not the natures required to check the development of tyrannical officialism, it will suffice to contemplate the direct proofs furnished by those classes among whom the socialistic idea most predominates, and who think themselves most interested in propagating it; the operative classes. These would constitute the great body of the socialistic organization, and their characters would determine its nature. What, then, are their characters as displayed in such organizations as they have already formed?

Instead of the selfishness of the employing classes and the selfishness of competition, we are to have the unselfishness of a mutually-aiding system. How far is this unselfishness now shown in the behavior of working men to one another? What shall we say to the rules limiting the numbers of new hands admitted into each trade, or to the rules which hinder ascent from inferior classes of workers to superior classes? One does not see in such regulations any of that altruism by which socialism is to be pervaded. Contrariwise, one sees a pursuit of private interests no less keen than among traders. Hence, unless we suppose that men’s natures will be suddenly exalted, we must conclude that the pursuit of private interests will sway the doings of all the component classes in a socialistic society.

With passive disregard of others’ claims goes active encroachment on them. “Be one of us or we will cut off your means of living,” is the usual threat of each trades-union to outsiders of the same trade. While their members insist on their own freedom to combine and fix the rates at which they will work (as they are perfectly justified in doing), the freedom of those who disagree with them is not only denied but the assertion of it is treated as a crime. Individuals who maintain their rights to make their own contracts are vilified as “blacklegs” and “traitors,” and meet with violence which would be merciless were there no legal penalties and no police.

The Closed Shop

Along with this trampling on the liberties of men of their own class, there goes peremptory dictation to the employing class: not prescribed terms and working arrangements only shall be conformed to, but none save those belonging to their body shall be employed; nay, in some cases, there shall be a strike if the employer carries on transactions with trading bodies that give work to nonunion men. Here, then, we are variously shown by trades-unions, or at any rate by the newer trades-unions, a determination to impose their regulations without regard to the rights of those who are to be coerced. So complete is the inversion of ideas and sentiments that maintenance of these rights is regarded as vicious and trespass upon them as virtuous.*

Along with this aggressiveness in one direction there goes submissiveness in another direction. The coercion of outsiders by unionists is paralleled only by their subjection to their leaders. That they may conquer in the struggle they surrender their individual liberties and individual judgments, and show no resentment, however dictatorial may be the rule exercised over them. Everywhere we see such subordination that bodies of workmen unanimously leave their work or return to it as their authorities order them. Nor do they resist when taxed all round to support strikers whose acts they may or may not approve, but instead, ill-treat recalcitrant members of their body who do not subscribe.

How Far Will They Go?

The traits thus shown must be operative in any new social organization, and the question to be asked is, What will result from their operation when they are relieved from all restraints? At present the separate bodies of men displaying them are in the midst of a society partially passive, partially antagonistic; are subject to the criticisms and reprobations of an independent press; and are under the control of law, enforced by police. If in these circumstances these bodies habitually take courses which override individual freedom, what will happen when, instead of being only scattered parts of the community, governed by their separate sets of regulators, they constitute the whole community, governed by a consolidated system of such regulators; when functionaries of all orders, including those who officer the press, form parts of the regulative organization; and when the law is both enacted and administered by this regulative organization?

The fanatical adherents of a social theory are capable of taking any measures, no matter how extreme, for carrying out their views: holding, like the merciless priesthoods of past times, that the end justifies the means. And when a general socialistic organization has been established, the vast, ramified, and consolidated body of those who direct its activities, using without check whatever coercion seems to them needful in the interests of the system (which will practically become their own interests) will have no hesitation in imposing their rigorous rule over the entire lives of the actual workers; until, eventually, there is developed an official oligarchy, with its various grades, exercising a tyranny more gigantic and more terrible than any which the world has seen.

*Marvellous are the conclusions men reach when once they desert the simple principle that each man should be allowed to pursue the objects of life, restrained only by the limits which the similar pursuits of their objects by other men impose. A generation ago we heard loud assertions of “the right to labor,” that is, the right to have labor provided; and there are still not a few who think the community bound to find work for each person. Compare this with the doctrine current in France at the time when the monarchical power culminated; namely, that “the right of working is a royal right which the prince can sell and the subjects must buy.” This contrast is startling enough; but a contrast still more startling is being provided for us. We now see a resuscitation of the despotic doctrine, differing only by the substitution of trades-unions for kings. For now that trades-unions are becoming universal, and each artisan has to pay prescribed monies to one or another of them, with the alternative of being a non-unionist to whom work is denied by force, it has come to this: that the right to labor is a trade-union right, which the trade-union can sell and the individual worker must buy!