In the 19th century, President Grover Cleveland set the record for putting the veto to good use. He used it to kill more bills than did all of his 22 predecessors combined. In one veto message, he famously declared that “though the people may support the government, it is not the duty of government to support the people.”

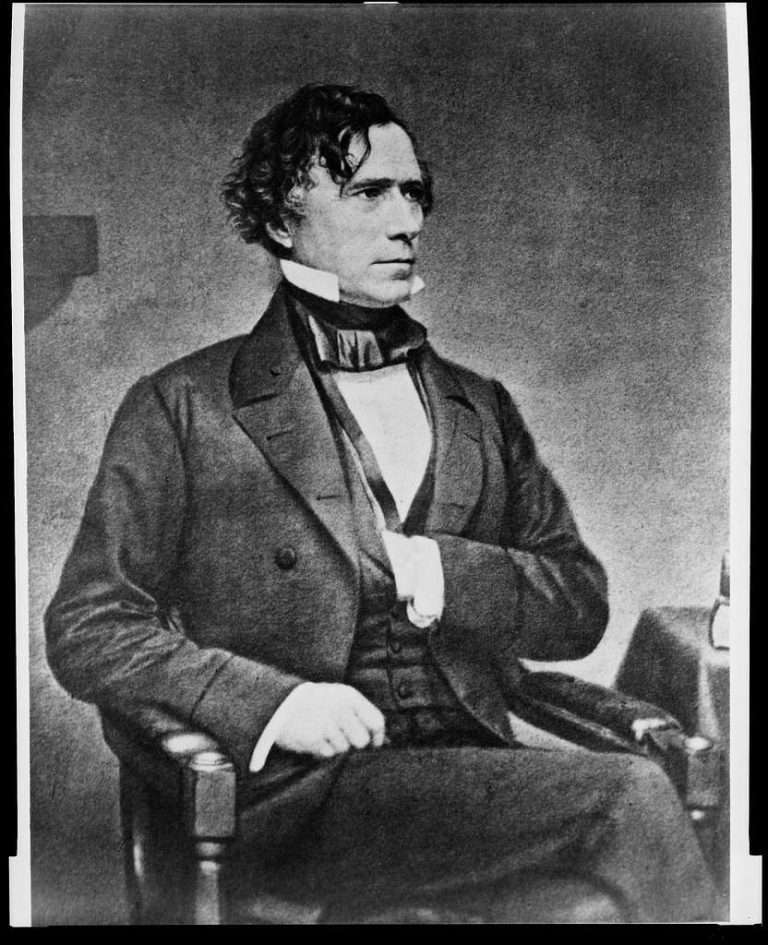

The only US President from the State of New Hampshire, Franklin Pierce (our 14th) cast just nine vetoes during his years in the White House, from 1853 to 1857. Five were overridden but not his most eloquent one. It’s one of my favorites, so here’s the story.

On May 3, 1854, President Pierce took great pains (and many pages) to justify his rejection of a bill to grant federal land or the cash equivalent to the States “for the benefit of indigent insane persons.” In the course of performing his Constitutional duty, he confessed feeling “compelled to resist the deep sympathies of my own heart in favor of the humane purpose sought to be accomplished.” He was concerned that he would be misunderstood and castigated as a man without compassion.

The bill proposed to set aside 12,225,000 acres of federal land. Ten million of those acres were earmarked for the benefit of the insane, and the remaining 2.225 million were to be sold for the benefit of the “blind, deaf, and dumb,” with proceeds parceled out to the states to build and maintain asylums.

One of his reasons for the veto was a profoundly “federalist” one, in the sense of preserving the balance of power between Washington and the rest of the country. “Are we too prone to forget,” he implored, “that the Federal Union is the creature of the States, not they of the Federal Union?”

If there is a role for government to complement the many private efforts and institutions assisting the mentally handicapped, why should the States pawn it off to the distant federal government? And don’t we run the risk, he asked, that “the fountains of charity” might dry up if government at any level gets involved in such things?

Any reader interested in a logical, even (dare I say it) piercing defense of adherence to the “enumerated powers” of the Constitution would do well to read this veto message.

President Pierce advanced an argument that might draw both chuckles and grimaces today. If Congress has the power to provide for the insane, he said, then, before you know it, Congress will assume it has the power to provide for the sane too—in any number of ways. He wrote:

If Congress may and ought to provide for any one of these objects, it may and ought to provide for them all. And if it be done in this case, what answer shall be given when Congress shall be called upon, as it doubtless will be, to pursue a similar course of legislation in the others?

More than a few nations in history have flushed themselves down the fiscal toilet with profligate, publicly financed, and politicized “compassion.” It starts small, but politicians have a way of thinking up new constituencies to throw money at and buy votes from. Today, 17 decades and $34 trillion in debt later, Franklin Pierce’s warnings are downright prophetic. Federal spending now subsidizes both the sane and the insane with sums unimaginable just a few generations ago.

Pierce’s veto set a precedent that lasted seventy years. After 1854, the federal government would not venture into large-scale social welfare legislation until the Great Depression. That event, brought on by none other than the government itself, opened the floodgates for federal social welfare spending.

Imagine if the spirit of Pierce’s veto had held for another seventy years. Perhaps the states would have expanded social welfare spending in the federal government’s absence. But since most states must balance their budgets and none can print money if they don’t, we would at least have been spared the harm from decades of federal deficits, debt, and printing press inflation.

Even one of our biggest spenders, Franklin Roosevelt, warned that federal profligacy couldn’t continue forever: “Any Government, like any family, can for a year spend a little more than it earns,” he said. “But you and I know that a continuation of that habit means the poorhouse.”

Franklin Pierce’s tumultuous one-term presidency was fraught with controversy over a wide range of issues, from the Kansas-Nebraska Act to slavery to subsidies for transcontinental railroads. His vice president, Rufus King, died one month into the job, leaving the position vacant for almost the entirety of Pierce’s term. As a retired ex-president, the man from New Hampshire poked a hornet’s nest when he publicly and vociferously opposed President Abraham Lincoln in the 1860s.

For example: While he urged Southern states to stay in the Union, Pierce also made it plain where he stood on the issue of war to hold the Union together: “I will never justify, sustain or in any way or to any extent uphold this cruel, heartless, aimless, unnecessary war.”

When Lincoln suspended habeas corpus (to allow the government to detain suspects without bringing formal charges in a court of law), Pierce criticized the move as blatantly unconstitutional. He argued that war did not grant the government the right to ignore civil liberties and the rule of law under the Constitution.

Whatever you may think of Franklin Pierce, a president whose name is all but forgotten, his 1854 veto of a bill to help the insane should be remembered and celebrated. It took courage to assert that not every “good cause” is a federal responsibility. And sometimes, the harm that flows from unconstrained spending takes a while to see and feel. We are now at the point that Pierce warned us would inevitably come if we threw caution to the wind.

Neither the Congress nor the President possesses the courage of a Franklin Pierce on the matter of spending, even as the national debt is on track to hit $50 trillion before this decade is out. That fact itself is a sign of insanity, far more of it than Pierce had to deal with.

Poorhouse, here we come.

Additional Reading:

Article I, Section 7: Interpretation by Nicholas Bagley and Thomas A. Smith

The Ten Best Presidential Vetoes in American History by Lawrence W. Reed

Grover Cleveland: One of America’s Greatest Presidents by Lawrence W. Reed