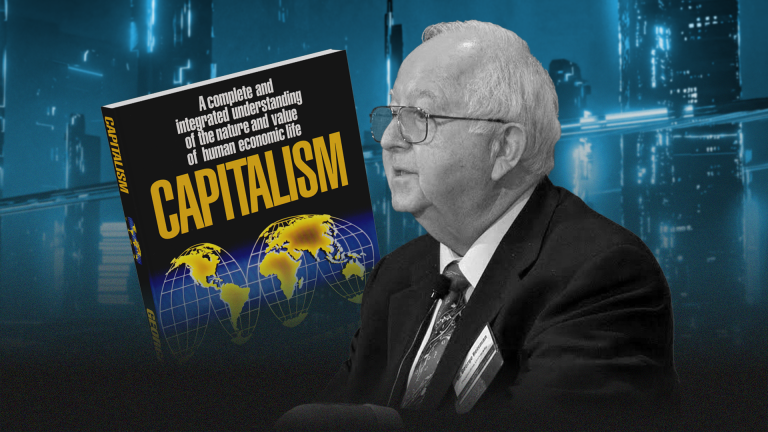

An excerpt from George Reisman’s ‘Capitalism: A Treatise on Economics.’

Editor’s Note: Our latest addition to the FEE ebook library is the monumental work by economist George Reisman: Capitalism: A Treatise on Economics. The following excerpt is taken from the beginning of Chapter 20.

The Importance of Capitalism as a Conscious Goal (cont’d)

The political proposals I make are short- and intermediate-range, as well as long-range in nature. I believe that it will take several generations to achieve a fully capitalist society, mainly because of the time required for the educational process. It will not be enough just to present our long-range goals. It will be necessary to advocate a whole intervening series of short- and intermediate-range goals whose enactment will represent progress toward our long-range goals. The major political task in the years ahead will be continuously to formulate such short and intermediate range goals, and to keep the country moving in the direction of full capitalism by means of their successive achievement. The short- and intermediate-range goals I offer are intended to illustrate principles of strategy and tactics and thus to serve as a pattern.

In the light of the preceding, it should scarcely be necessary to say that at no time should the advocacy of sound principles be sacrificed to notions of political expediency, advanced under misguided ideas about what is “practical.” The only practical course is to name and defend true principles and then seek to win over public opinion to the support of such principles. It is never to accept the untrue principles that guide public opinion at the moment and design and advocate programs that pander to the errors of the public. Such a procedure is to abandon the fight for any fundamental or significant change—namely, a change in people’s ideas—and to reinforce the errors we want to combat.

It is definitely not impractical to explain to people that if they want to live and prosper, they must adopt capitalism. It would not be impractical to do so even if for a very long time most people simply refused to listen and went on supporting policies that are against their interests. In such a case, it would not be the advocates of capitalism who were impractical, for they would be pursuing the only course that is capable of working, namely, explaining to people what they must do if they are in fact to succeed. Rather it would be the mass of people—perhaps, indeed, the entire rest of the society—that would be impractical, pursuing as it did goals which are self-destructive and refusing to hear of constructive alternatives. If, to use an analogy from the world of engineering and business, someone knows how to build an airplane or a tractor that people could afford and greatly benefit from, but is not listened to, such a person is not at all impractical because others refuse to listen to his ideas that would greatly benefit them. Rather it is those others, whatever their number, who are impractical. In the political-economic realm, it is the current state of public opinion that is impractical: it expects that men can live in a modern economic system while destroying the foundations of that system—that, for example, they can have rising prosperity while destroying the incentives and the means of the businessmen and capitalists who are to provide the prosperity. The advocates of capitalism, who tell people that the opposite is true and that the opposite policy is necessary, are not impractical. They are eminently the advocates of practicality—of what is achievable in, and by the nature of, reality.

It is the grossest compounding of confusions to suggest that those who know truths that masses of impractical people refuse to hear, accept error as an unalterable given for the sake of which they must abandon or “bend” their knowledge of the truth. Nothing could be more impractical, elevating as it does, error above truth and making knowledge subordinate to ignorance. The essence of true political practicality consists of clearly naming and explaining the long-range political program that promotes human life and well being—i.e., capitalism—and then step by step moving toward the fullest and most consistent achievement of that goal. That the initial effect of naming the right goal and course may be to shock masses of unenlightened people and invoke their displeasure should be welcomed. That will be the first step in awakening them from their ignorance.

It should not be surprising that those who fear the effects of the open advocacy of capitalism are themselves highly deficient in their knowledge of capitalism. They fear to evoke the displeasure of the ignorant because they do not know enough about capitalism to know what to say in the face of such displeasure. Their ignorance on this score, I believe, is the result of an unwillingness to acquire a sufficient combination of knowledge of political philosophy and economic theory, above all, of economic theory. Remnants of the mind-body dichotomy in their thinking prevent them from fully grasping the intellectual—indeed, the profoundly philosophical—value of a subject as “materialistic” as economics. To be successful, the advocates of capitalism must immerse themselves in the study of economic theory.

The Capitalist Society and a Political Program for Achieving It

The capitalist society we want to achieve is a society in which individual rights are consistently and scrupulously respected—in which, as Ayn Rand put it, the initiation of physical force is barred from human relationships. We want a society in which the role of government is limited to the protection of individual rights, and in which, therefore, the government uses force only in defense and retaliation against the initiation of force. We want a society in which property rights are recognized as among the foremost human rights—a society in which no one is made to suffer for his success by being sacrificed to the envy of others, a society in which all land, natural resources, and other means of production are privately owned. In such a society, the size of government would be less than a tenth of what it now is in terms of government spending. Most of the government as it now exists would be swept away: virtually all of the alphabet agencies and all of the cabinet departments with the exceptions of defense, state, justice, and treasury. All that would remain is a radically reduced executive branch, and legislative and judicial branches with radically reduced powers. To the law-abiding citizen of such a society, the government would appear essentially as a “night watchman,” dutifully and quietly going about its appointed rounds so that the citizenry could rest secure in the knowledge that their persons and property were free from aggression. Only in the lives of common criminals and foreign aggressor states would the presence of the government bulk large.

If these brief remarks can serve as a description of the capitalist society we want to achieve, let us now turn to a series of political proposals for its actual achievement. I group the proposals under seven headings: Privatization of Property, Freedom of Production and Trade, Abolition of the Welfare State, Abolition of the Income and Inheritance Taxes, Establishment of Gold as Money, Procapitalist Foreign Policy, and Separation of State from Education, Science, and Religion. Under each of these heads, I develop specific issues and programs each of which deserves to be fought for and which, in being fought for, would serve to promote the spread of our entire political-economic philosophy.