What the Azores teach us about sustainability.

The archipelago of the Azores, a Portuguese territory located in the North Atlantic between Europe and North America, is frequently celebrated for its natural beauty, volcanic landscapes, and the idyllic image of dairy cows dominating the green islands. This tourist imagery, however, hides a historically difficult economic reality.

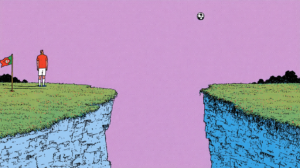

The geographic location of the Azores, marked by insularity, market isolation, and natural limitations on agricultural production, has imposed deep economic costs. For decades, the archipelago has concentrated some of the lowest income levels in the country, including the municipality of Rabo de Peixe, frequently cited as one of the poorest in Portugal. Despite Portugal’s democratic government, the Azores have benefited from few structural reforms aimed at economic liberalization. An emblematic example was air transport, which remained heavily protected for decades and only began to be significantly liberalized starting in 2015, both for inter-island connections and links to the mainland.

For many Azoreans, being born in the archipelago meant living for generations with very limited economic opportunities. They had to choose between staying with little chance of social mobility or emigrating. Thousands chose to leave, especially for the United States, where they settled in large numbers in the state of Massachusetts. Cities like New Bedford and Fall River (the latter frequently called the 10th island of the Azores) still preserve a vivid memory of this connection today, visible in the New Bedford Whaling Museum dedicated to whaling and maritime history, where the Azorean presence is central.

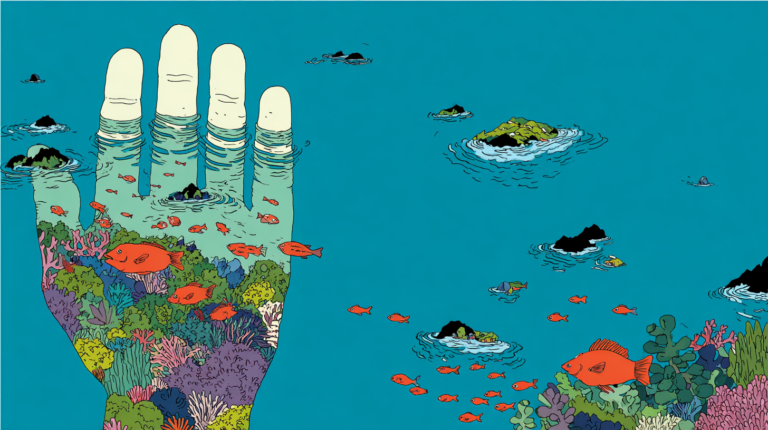

For those who stayed, the sea was for a long time the main, and sometimes the only, source of subsistence.

For decades, islands like Faial depended heavily on whaling, a central activity for the local economy. Whale oil was an essential energy resource in the Atlantic world, used for lighting in major European cities, including London. With the decline of this industry and the subsequent ban on whaling, many of these communities were forced to adapt, converting maritime knowledge and infrastructure into tourism-related activities, particularly cetacean watching.

This direct dependence on the sea created an economic system based on immediate incentives. Those who exploit marine resources in the Azores live within the consequences of their own decisions: overexploitation has rapid, visible, and local effects. Fishing, carried out mostly on a small scale and repeatedly by the same communities, generated prudent practices long before modern regulatory frameworks existed.

This model helps explain why, in recent decades, the blue economy has stood out from the rest of the regional economy, accounting for nearly 10% of the regional Gross Value Added (GVA) in 2022.

This success is due to local resource management and not to a centralized plan at the European level.

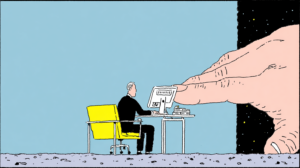

It is precisely here that tension arises with the European regulatory framework. The Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) was designed to manage large industrial fleets on a continental scale, with rigid national quotas set in Brussels and impacts diluted over time. In the Azores, although the CFP is applied, its weight is much smaller since the fleet is almost entirely artisanal (fewer than 700 vessels, most small), the population is reduced (around 240,000 inhabitants), and insularity already imposes close and immediate resource management.

As an Outermost Region, the Azores benefit from adaptations and derogations under Article 349 of the EU Treaty, but in this case the EU does nothing more than grant exceptions to dynamics that never needed these regulations in the first place. This community self-regulates, with the Regional Government itself establishing additional quotas and limits per species (through annual ordinances), prohibiting practices such as bottom trawling in the local EEZ, and adjusting rules based on insular reality. Those who overexploit feel the consequences in months, not years.

Rules designed to curb abuses in industrial fleets end up imposing some fixed costs (reports, monitoring), but they do not “ruin” the system: the proximity between decision and consequence preserves pre-existing prudent practices, allows rapid adaptation, and sustains the growth of the blue economy.

The Azorean case shows that sustainability arises more from local responsibility than from distant centralized control. And this should be an example that public policies work better when they respect, recognize, and preserve the experience of those who live close to the consequences of their actions, and that the European Union should stop interfering so intensely in the management of natural resources of its Member States.

Here echoes the great lesson of Adam Smith: when each person decides based on what best serves his or her interests, and feels the consequences directly, the economy tends to prosper.

Letting people free to pursue their well-being, in a context of real responsibility, generates wealth and sustainability simultaneously.