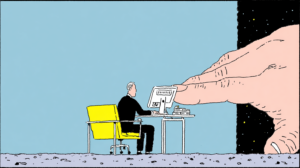

The cost of central planning.

After decades of subsidizing expansion, Brussels is now paying to destroy vineyards, without fixing the distortions it created.

The European Union is paying to uproot vineyards. The new Wine Package, proposed in March 2025 with a provisional agreement reached in December 2025, proposes among several measures, the possibility of using EU funds for the voluntary destruction of productive vines, which represents the most visible sign of a market distortion created by decades of intervention from Brussels.

Successive policies supporting the wine sector progressively disconnected production from market signals. The result was a growing imbalance, marked by persistent surpluses and, later, by subsidies aimed at vineyard removal itself. It is within this context that the European Union now presents the Wine Package, yet another regulation which claims to solve a problem that previous policies helped to create.

When the Common Agricultural Policy was established, it was quickly determined that one of its core objectives would be the protection of farmers, ensuring stable incomes and food security. In the wine sector, this logic translated into strong interventionism aimed at expanding and stabilizing production.

For decades, Brussels subsidized vineyard planting, protected minimum prices, and absorbed producers’ economic risk, disconnecting production decisions from signals of demand. Producing more ceased to be an economic choice and became a politically safe decision.

This approach created a structural market distortion. As wine consumption began to decline across Europe for demographic, cultural, and economic reasons, the artificially incentivized productive structure remained intact and unable to adjust.

It was in this context that, during the 1980s and 1990s, the first major shock occurred, known as the wine lake: massive wine surpluses with no outlet. Even then, Brussels treated this episode as an isolated and temporary phenomenon, ignoring the fact that it was the direct consequence of existing policies. By persisting with the same strategies, the problem ceased to be episodic and became structural.

In the early 2000s, the European Union was finally forced to recognize that the wine crisis was not temporary. However, instead of removing production incentives and restoring the market’s adjustment function, it opted for a new form of intervention: subsidizing the voluntary uprooting of vineyards. The decision to destroy productive capacity ceased to be economic and became administrative, decreed from the European political center, with profound effects across several countries.

This model, presented as temporary, set a dangerous precedent. Rather than allowing less viable producers to exit the market through prices and economic choice, the state began paying for withdrawal, subsidizing the costs of adjustment and normalizing the idea that the correction of public policy errors should be financed with more public money.

This policy did not solve the underlying problem. It merely reduced cultivated area temporarily, while leaving intact the regulatory architecture which had created the initial distortion. The sector became trapped in a cycle of incentivized expansion, predictable crisis, and administrative correction.

It is within this framework that the Wine Package emerges as the European Union’s latest set of measures for the wine sector. The package relies on an administratively planned reduction of supply through financial incentives for vineyard uprooting, complemented by regulatory adjustments, temporary support measures, and crisis management instruments. Instead of allowing the market to adjust to declining consumption, Brussels once again opts for the destruction of productive capacity as a policy tool. Although the package includes support measures and environmental framing, its central axis remains the administrative reduction of supply.

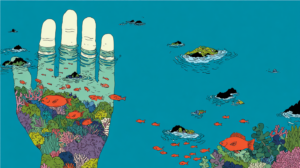

The impact of these decisions is not marginal. The European wine sector represents a significant share of the European Union’s economy, sustaining approximately 2.9 million direct and indirect jobs and contributing more than €130 billion to EU GDP.

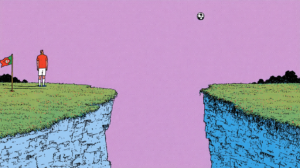

The effects of this policy vary significantly by territory, but its uniform and uncritical application ignores distinct realities, such as Bordeaux in France and the Douro in Portugal.

Bordeaux faces a genuine surplus problem. In November 2025, France announced a national aid package of €130 million specifically for the permanent uprooting of vineyards in vulnerable regions like Bordeaux.

The Douro does not. This region has historically focused on exports, value creation, and production control. Even so, it will be forced to bear the consequences of yet another one-size-fits-all regulation. Where no imbalance previously existed, one will now be introduced.

In the Douro, the consequences of the Wine Package extend far beyond reduced production. Vineyard uprooting destroys irreversible agricultural capital, weakens small producers, and accelerates the abandonment of a territory where viticulture is often the only viable economic activity. Unlike regions characterized by structural surpluses, the Douro does not face a problem of excessive production, but rather one of regulatory pressure and rising costs. Applying a uniform policy to this reality amounts to importing a crisis which did not previously exist, undermining the economic, social, and landscape sustainability of one of Europe’s most emblematic wine regions.

The European Union continues to insist on the same error which led the wine sector to this point. The systematic replacement of market adjustment with administrative decision-making does not correct distortions; it entrenches them. The solution lies in restoring producers’ and regions’ capacity to adapt, respecting regional diversity and the principle of subsidiarity. As long as Brussels continues to manage wine as a centralized technical problem, it will continue to create crises where none previously existed.