A Valuable Contribution to Any Student of Liberty's Library

Free Press 1996 318 pages $15.00

Mr. Steelman is a staff writer at the Cato Institute.

The free-market movement in the United States has prospered tremendously over the past 20 years. Dozens of market-oriented think tanks and journals have been created, and an increasing number of students are becoming interested in the ideas of liberty. The Concise Conservative Encyclopedia provides a valuable and easy-to-read introduction to the ideas, individuals, and organizations that have shaped this burgeoning intellectual movement.

Miner’s book contains 200 brief entries, an afterword by the author, and five succinct essays on the origins of conservative thought, ranging from antiquity to the modern era. Those essays are written by Carnes Lord, Jacob Neusner, James Schall, S.J., Peter Stanlis, and Charles Kesler.

In the preface, Miner argues that the “purpose of a ‘reader’s encyclopedia’ such as this one is not to provide the last word on the topics and people it covers, but to offer the inquiring reader just enough information about the subject in question to enable him to go on reading in some other book with a modicum of improved perspective.” Toward that end he has succeeded marvelously.

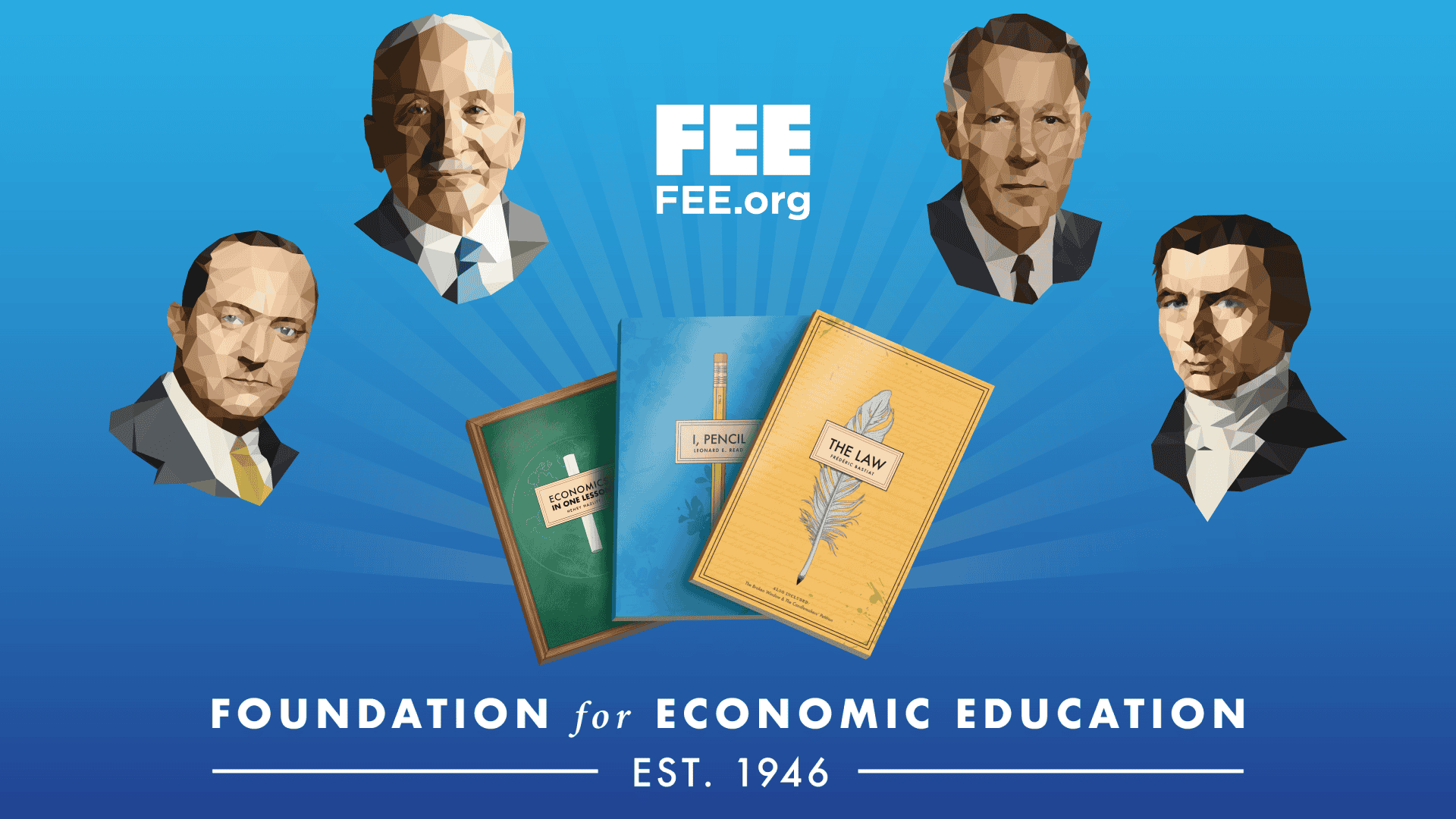

The entries have been chosen wisely and the author has given more than adequate attention to all the major strains of modern free-market thought, including classical liberalism. Every major classical liberal and libertarian figure—including Mises, Hazlitt, Bastiat, Friedman, and Hayek, to mention but a few—is incisively and intelligently profiled. In addition, Miner has included entries for a number of other individuals and institutions that readers of The Freeman will undoubtedly be familiar with, but that many nonlibertarians will not. Among those are Frank Chodorov, Bertrand de Jouvenel, and Felix Morley. The book also contains brief, yet insightful, descriptions of the Austrian, Chicago, and Virginia schools of economics. And Miner doesn’t shy away from discussing differences of opinion on the Right. He discusses the debates over an interventionist foreign policy and free trade, and he deals with the seeming divide between traditionalism and libertarianism, which he argues has been overblown.

For newcomers to free-market thought, his suggested readings at the end of each entry will be valuable—although there are a few exceptions to that rule. For example, the lone book by Mises that he has recommended is Human Action. While there can be little question that Human Action is the most comprehensive statement of Mises’s worldview, how many beginners are going to be able to actually get through it? Listing, for example, Liberalism or Planning for Freedom as well would have been more helpful.

Moreover, there are some exclusions that seem a bit puzzling. The Institute for Humane Studies, the Cato Institute, and the Volker Fund do not receive individual listings, nor do Israel Kirzner and Richard Epstein, two giants of free-market scholarship.

Despite those problems, The Concise Conservative Encyclopedia is a tremendous improvement over its two principal competitors: Right Minds: A Sourcebook of American Conservative Thought by Gregory Wolfe and A Dictionary of American Conservatism by Louis Filler. It belongs in the library of every student of liberty, beginner or veteran.