From risky surgery to lithotripsy

Samuel Pepys Diary, 1660–1669.

About three weeks ago, I had a lithotripsy to break up some kidney stones. While I was under general anesthetic for an hour or so, the doctor used ultrasound waves to break a few larger stones into tiny pieces so they wouldn’t cause me further pain. I woke up in some discomfort, took Vicodin for a couple days, and was back in the office three days later.

Friends and family who heard descriptions of the ultrasound pummeling, or who saw me wincing the day after the procedure, were sympathetic about the brutality of what had to be done in order to fix me. But I have no scar, because there was no need for surgery. I didn’t even have any bruising. And though I complained a bit, it really wasn’t all that bad. And I’m perfectly fine now.

I wouldn’t ordinarily use this column to talk about my health. We’re supposed to be talking about books. But nearly 15 years ago, I wrote a dissertation on literary representations of early modern medicine, and ever since working on that project, I’ve been interested in medical history and in the way that treatments have improved over time.

Kidney stones are a particularly fascinating illness for someone interested in historical literature about sickness. One of the great 17th-century diarists, Samuel Pepys, suffered from bladder stones, which are more or less the same thing. And he wrote a lot about them.

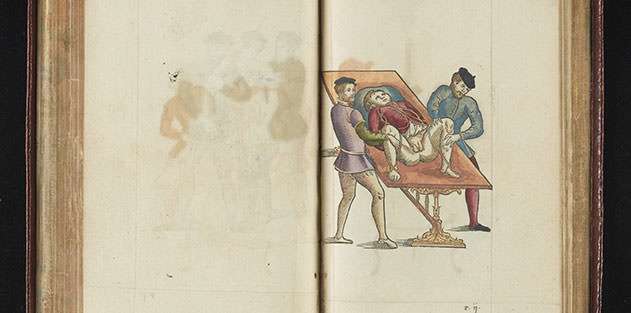

About two years before Pepys began his famous diary, he was “cut of the stone,” or operated on for bladder stones. The operation was performed, as was usual, at a relative’s home, by a surgeon hired for the occasion. With no anesthetic, Pepys was held down by several strong friends or servants while the surgeon cut into some of the most intimate parts of his flesh and removed the stone. Not only did Pepys suffer far more than I did, he also expected to die. Before any serious notions of sanitation, before germ theory, and before anesthetic, this was not at all an exaggerated fear.

Because Pepys got lucky—his friend kept a clean house; he had a good surgeon; his surgeon had a new set of tools that had not been used on a previous patient, which lowered Pepys’ chance of infection—he lived and he thrived. But he was so cognizant of the risks he had faced that every year thereafter he kept a personal holiday on the day that he faced his surgery. On March 26, 1660, he wrote, “This year it is two years since it pleased God that I was cut of the stone at Mrs. Turner’s in Salisbury-court. And did resolve while I live to keep it a festival, as I did the last year at my house, and for ever to have Mrs. Turner and her company with me.”

The success of the operation was so significant for Pepys that he didn’t just annually mark the day he survived the operation. He also marked the day he felt fully recovered. On May 1, 1660, for example, he takes time to write, “This day I do count myself to have had full two years of perfect cure of the stone, for which God of heaven be blessed.”

When I was in graduate school and spending all my time thinking about Pepys and his stones and other writers and their headaches, their fevers, their infected belly buttons, and so on, I would occasionally be asked why I wanted to spend my time thinking about something as grisly and comically antiquated as early modern medicine. I agreed that it’s hard to study this stuff and not be horrified and amused. But the modern era’s medical advances are not reason to look to the past with arrogance and complacency. Our 21st-century medicine is the best medicine we can provide with the technology and knowledge that we now have. So was the 17th-century medicine that Pepys experienced—even though it looks to our modern eyes as if the major medical skill of the time was the ability to make people bleed, vomit, or excrete copiously, in hopes of “getting the bad humours out.” My hope is that in 350 years, the procedure my doctor used for my kidney stones will sound as barbaric to my descendants as Pepys’ procedure sounds to us. I hope they’re astounded that I would bother to write a column about something so trivial.

Deirdre McCloskey and other economists remind us often and powerfully that humans have seen unimaginable increases in wealth of all kinds in the centuries between Pepys’ day and our own. Surely, the differences between Pepys’ stones and mine are a part of that wealth. Surely this is one of the uses of history and of literature. Reading wisely, we can take ourselves out of our own world and see how far we have come. And we can begin to think about how far we may be able to go.

I even had to check my calendar the other day—because unlike Pepys, I couldn’t quite remember which day I had been treated.