Hayes believed in sound character and sound money.

Rutherford B. Hayes, America’s nineteenth president (1877–1881), is generally dismissed as a minor, even below-average president. Matthew Josephson, the journalist-chronicler of the late 1800s, insisted that Hayes had “no capacity for … large-minded leadership.” Other historians have written him off as just another cipher among a string of forgettable chief executives of the Gilded Age.

But the truth is that Hayes was a strong and principled leader of firm character, who, during a critical time in history, shored up the country’s finances. His contributions to restoring American credit are worth noting today.

Hayes was a small-town Ohio lawyer until his Civil War exploits earned him a promotion to brigadier general and won him a congressional seat after the war. After one term in Congress, Hayes was elected three times as governor of Ohio. In 1876 he won the Republican nomination for president, and during the campaign that followed he defeated Governor Samuel Tilden of New York in a controversial election. Tilden won the popular vote, but Hayes won the electoral vote after a special commission awarded him the disputed states of Florida, South Carolina, and Louisiana.

Severe Inflation

Once in the White House, Hayes withdrew northern troops from the South and thus ended Reconstruction. But the enormous financial debts from the Civil War still lingered. That war had been so costly that the Union could not secure the cash (that is, specie) to fight it. Congress and President Lincoln covered expenses by issuing over $400 million in greenbacks, which would not be redeemable in gold until some future date. The flood of greenbacks caused inflation and chaos—merchants wanted specie, not paper that someday might be redeemed.

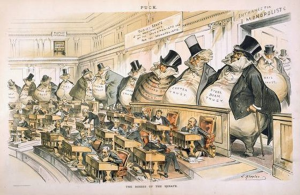

Many Americans, especially debtors who liked the idea of repaying loans in inflated currency, welcomed the greenbacks and wanted more to be printed. The problem with that, apart from serious inflation, was that foreigners were refusing to buy American debt, which raised the interest costs on the almost $2 billion that the Union borrowed to fight the war.

In 1875, Congress had promised to redeem the greenbacks for gold in four years and Hayes ran his campaign on a pledge to fulfill that promise. “Low rates of interest on the vast indebtedness we must carry for many years,” Hayes said, “is the important end to be kept in view.”

Hayes was appalled at the persistent efforts of inflationists to tamper with the currency.

As president, therefore, Hayes prepared to retire the greenbacks. He had budget surpluses every year in office, and he used these extra funds to help build up a gold reserve to pay off the greenbacks. So effective was Hayes at this task that when the official government redemption date (January 2, 1879) came around, few people stepped forward to get gold for their greenbacks. Confidence in U.S. credit was such that most people traded greenbacks at face value with confidence that gold would be in the Treasury if they ever wanted it.

Having solved the greenback problem, Hayes also faced a crisis with silver. From the beginning of U.S. history, gold and silver coins (and bullion) had circulated to pay debts, to conduct trade, and to transact business. Silver, of course, is more plentiful than gold, and the ratio had been 15 or 16 ounces of silver to 1 ounce of gold. The U.S. Treasury, in fact, minted coins and traded the metals at 16 to 1 during much of the 1800s. But that all stopped after the Civil War.

The problem was that active mining in the American West was yielding much more silver than gold.

Also, the demand for silver was down because the rest of the world was beating a path to a monometallic gold standard. By the end of the 1800s, with silver prices down, it took about 32 ounces to buy one ounce of gold. The silver miners believed this devaluation of their metal was unfair. Those who favored inflation were happy to agree: If the government would stabilize the ratio at 16 to 1, debtors could repay in inflated silver dollars instead of gold. Flooding the market with silver (fixed at 16 to 1) would have the same effect as running greenbacks off the printing press.

Hayes was appalled at the persistent efforts of inflationists to tamper with the currency. “Expediency and justice both demand honest coinage,” Hayes insisted. Sound currency and sound character were one and the same to Hayes. “A currency worth less than it purports to be worth,” Hayes observed, “will in the end defraud not only creditors, but all who are engaged in legitimate business, and none more surely than those who are dependent on their daily labor for their daily bread.”

Free Silver

The inflationists lobbied hard with their politicians for what was called “free silver,” which was short for the free and unlimited coinage at the fixed ratio. They couldn’t muster the votes, but they did support the Bland-Allison Act in 1878.

Under that bill, Congress would be obligated to buy at least $2 million (and up to $4 million) worth of silver and mint it into special dollars of almost one ounce. Such “dollars” in 1878 contained only about 90–92 cents worth of silver, and Hayes was dismayed that Congress would even consider tampering with U.S. coins that way. He promised to veto any “measure which stains our credit.” When Congress passed the act anyway, Hayes vetoed it. Congress, however, overrode Hayes with a two-thirds vote, and the Bland-Allison bill became law.

Hayes began efforts to make government bureaucrats work more honestly and efficiently.

The presence of these new silver dollars bothered Hayes, but American credit remained strong throughout the world. The greenback problem was under control, and the government continued to retire the Civil War debt through annual budget surpluses. In 1880, for example, federal revenue was $333.5 million, which was $65.9 million—almost 20 percent—more than expenses. The biggest item in the federal budget was $95.8 million for interest on the debt. With diligence, Hayes had renegotiated much of this debt from 6 to 5 and sometimes 4 percent.

In an effort to slash future expenses, Hayes began efforts to make government bureaucrats work more honestly and efficiently. In the New York Customs House, for example, some officials were extorting payments from importers, and other officials were drawing salaries but doing almost no work. Since President Grant, Hayes’s predecessor, had suffered greatly from the shenanigans of dishonest government officials, Hayes tried extra hard to reform the civil service and make sure government graft was kept to a minimum.

Finally, Hayes showed balance in his administration. When, during a massive railroad strike in 1877, a state governor asked him to send in federal troops to preserve order, Hayes obliged. But he would not use federal troops to break the strike.

Hayes was a constitutional president. He believed in an executive strong enough to veto bad legislation, but he did not want to expand executive powers beyond what the Constitution specified. Congress was where laws needed to originate and where most political debate needed to take place.

Politics, to Hayes, was not a career. After serving one term as president, he happily stepped down and returned to private life.