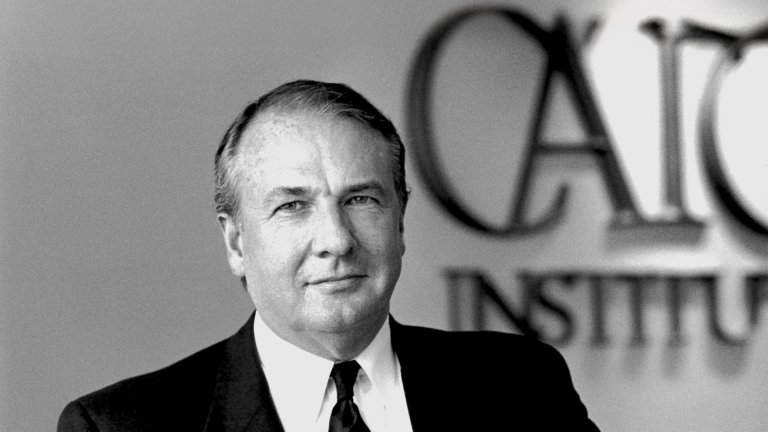

A leader for liberty.

Ed Crane, the self-described Beloved Founder of the Cato Institute, passed away on February 10. He should be remembered first and foremost as an institution builder. In his 30-plus years as President of Cato, Ed took libertarian ideas from the fringe to the mainstream. That was no trivial accomplishment, given that so many of us in the liberty movement are nonconformists (organizing libertarians is akin to herding cats).

I was fortunate to work at Cato for about 11 years, with Ed as my ultimate boss for the first half of my tenure. However, boss is the wrong word. Ed and his leadership team did not micromanage employees. They hired philosophically motivated people and expected them to be smart enough to figure out how best to spread the message of freedom. Think of this as the libertarian version of Shakespeare’s line, “Cry ‘Havoc!’, and let slip the dogs of war.”

One of my first memories of Ed was when he subjected me to a friendly but serious interrogation about “supply-side economics.” He was worried that I might think that the only important goal of fiscal policy was lower tax rates. Or, even worse, I might be one of those supply-siders who thought lower tax rates were good because the resulting economic growth would generate more revenue for the government.

Needless to say, I assured him that my goal was to be at the growth-maximizing point on the Laffer Curve, not the peak of the curve where revenues are maximized. And that meant very low rates, if not the complete abolition of income tax. Equally important, I made clear that my goal was a much smaller federal government, consuming only 2–3% of GDP, just as the Founding Fathers intended.

I also fondly remember that he instinctively understood the importance of protecting and preserving tax competition, which occurs when politicians face pressure to lower tax rates (or not to raise tax rates) because of the fear that jobs and investment would otherwise migrate across borders. Not many people understood that tax competition was needed to limit the greed of the political class. And even fewer were willing to defend so-called tax havens against demagoguery and attacks by left-leaning international bureaucracies such as the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. But Ed knew from the start that an “OPEC for politicians” would be a horrible development.

Ed made sure that Cato was on the cutting edge of major policy developments. Very few people realize how close we came to getting personal retirement accounts about 20–30 years ago. And even fewer people know that Cato was the institution that did the most to popularize the idea. One of his best ideas was to enlist the help of José Piñera, who implemented personal accounts in Chile and has since become a global apostle for this much-needed reform. Under Ed’s leadership, Cato also supported reforms of other entitlements such as Medicare and Medicaid (and we came very close to success about 10–15 years ago).

Another admirable feature of Ed’s leadership is that Cato was never partisan. Yes, depending on the issue, some of us worked more closely with Republicans, and others of us worked more closely with Democrats. But in all cases, the top priority was advancing the cause of limited government and personal liberty. There was never the slightest suggestion that our work should be tailored to advance the interest of any politician or any party.

From a personal perspective, one of my fondest memories is the periodic dinners that I would enjoy with Ed, Walter Williams, and Richard Rahn. As the youngster of the group, it was a bit daunting to hang out with three guys who would be obvious candidates if anyone ever creates a libertarian Mount Rushmore. Sadly, Walter passed in 2020, and now we’ve lost Ed. These are genuine losses, especially for those of us lucky enough to have known them.

I hope that Cato figures out an appropriate way of memorializing Ed. A libertarian Mount Rushmore is probably not practical, but I’m sure that some very bright people there are already coming up with ideas. Very few people make a difference in world history. Edward Harrison Crane was one of those people.