Saturday, October 1, 1994

Ideas and Consequences: The Immigration Problem

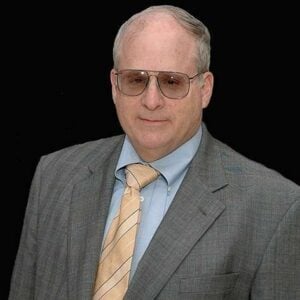

A rising tide of anti-immigrant feeling is washing over America, leaving in its wake a misinformed public and the potential for harmful new laws. Many Americans seem to be thinking, “I'm glad my grandparents made it over from the old country, but now that we're here, let's shut the door to any more of those foreigners.” People opting to come to our shores is a generally positive development; in fact, it's what made it possible to carve this great country from a wilderness in the first place. The lessons of free immigration may be drowned out by a host of current concerns, but they are as real and vital as ever. In a widely acclaimed 1989 book entitled The Economic Consequences of Immigration, University of Maryland Professor Julian Simon demolished virtually every fallacy of the seal-the- borders mentality. He proved that immigrants do not subtract from the total number of available jobs, are net contributors to the public treasury, do not commit more crimes than natives, and generally work harder, save more, and are more likely to create businesses than native Americans. All things considered, newcomers add wealth, culture, and human capital to the economy. Simon has demonstrated that immigrants are really not the huddled masses, helpless and dependent, that many people think. Instead, they are usually young and vigorous adults with excellent earnings potential. His detailed studies show that on balance, even accounting for all public welfare and other government “social service” costs imposed by our homegrown nanny state, each immigrant still contributes far more than he “takes” by being here. In a 1990 Wall Street Journal article, Simon made another point worth repeating. The foreign- born population in the United States today is only about 6 percent—less than the proportion in such countries as Britain, France, and West Germany, and “vastly lower” than in Australia and Canada. We are not a nation of immigrants. We are a nation of the descendants of immigrants. People are only economic problems in systems which deny them the ability to be enterprising, to use their talents and ambitions to produce more wealth than they consume. Systems that encourage sloth and idleness with generous public welfare transform people—natives as well as immigrants—into dependents who subtract more than they add to the economy and society. What often is perceived as a crisis of immigration is really a crisis of our own politicized and half- socialized economy, which attracts some foreigners because of the subsidies it grants rather than with the opportunities for self-reliance it offers. Sometimes, American foreign policy has generated the very waves of immigration that so many in our government lament. In recent months, far more Haitians fled their country for our shores because of an American trade embargo against Haiti than fled because the military dictatorship targeted them for persecution. (After all, Haiti has almost always had a military dictatorship but when its people starve because of embargoes, they have to go somewhere.) In any event, it seems self-evident to me that of the many pressing problems facing America these days, none are caused by immigration or immigrants. Foreigners didn't impose on us an expensive state education monopoly that doesn't educate; red-blooded Americans did. A Congress that can't balance its own budget at the same time it attempts to micromanage every aspect of other people's businesses is not made up of Haitian boat people. It wasn't Korean-born shopkeepers who set fire to downtown Los Angeles in 1992. The case for free immigration today is strongest when it is coupled with the general argument for a free society, private property, and individual rights. I can think of no better way to illustrate this than by a personal example.