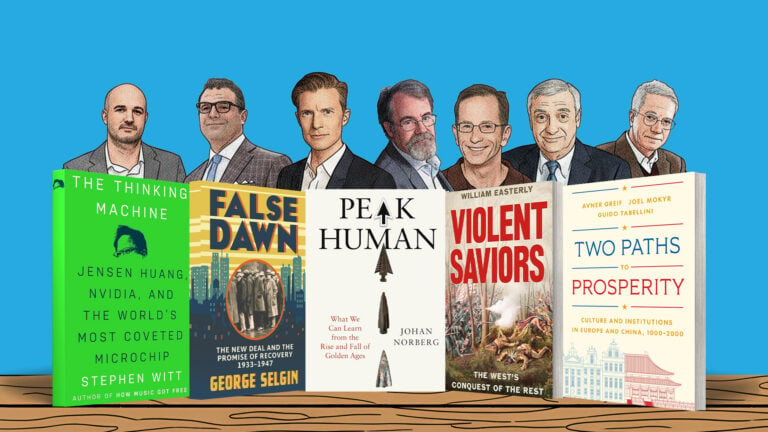

A selection of works that defend open societies and innovation.

Discovering new works in economics is always a pleasure, and this year offered a generous harvest. At a time when arguments against free trade and in favor of restricting innovation have gained traction, 2025 gave us a strong intellectual arsenal to defend openness, free markets, and creative destruction.

My five favorite books nourish our sense of wonder, deepen our understanding, and strengthen our appreciation for open societies. Each, in its own way, celebrates freedom with rigorous argument and offers sharp criticism of various schemes of central planning or political control.

1. Peak Human, by Johan Norberg

Johan Norberg remains one of the most eloquent pro-capitalist writers of our time. Peak Human condenses and amplifies the message he developed in earlier works like In Defense of Global Capitalism, Progress, Open, and The Capitalist Manifesto. Here, Norberg revisits seven “golden ages” of humanity—from Athens and the Abbasid Caliphate to Renaissance Italy and the Dutch Republic—to identify the common trait that links them all: openness.

Humanity reaches new heights when societies embrace openness to the world, commercial exchange, cultural creativity, science, property rights, and the freedom to experiment. As he writes, “A golden age is associated with a culture of optimism, which encourages people to explore new knowledge, experiment with new methods and technologies, and exchange the results with others.”

But Norberg also sounds a warning: societies collapse when they forget the institutional and cultural foundations that made their progress possible and instead embrace protectionism and control.

2. False Dawn, by George Selgin

The Great Depression was the most catastrophic economic event in U.S. history, and unsurprisingly it has generated an enormous literature. From Friedman and Schwartz’s The Great Contraction to Amity Shlaes’s The Forgotten Man and Jim Powell’s FDR’s Folly, we possess considerable evidence about the policy mistakes that deepened and prolonged the crisis.

George Selgin’s False Dawn: The New Deal and the Promise of Recovery is a major contribution to this tradition. With extraordinary scholarship and intellectual fairness, Selgin documents every major New Deal initiative: the entire suite of policies and political decisions that defined Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s administration.

His conclusion is unequivocal: the two pillars of the New Deal’s recovery strategy—the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) and the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA)—failed, and worse, reversed early signs of recovery. The AAA deliberately destroyed crops to raise agricultural prices; the NIRA cartelized industries, legalized collusion, and pushed wages upward artificially, reducing output and employment in the middle of an economic collapse.

Combined with economist Robert Higgs’s theory of “regime uncertainty,” Selgin’s analysis leads to a broader insight: abrupt changes in the rules of the game and Roosevelt’s threats against businesses paralyzed investment. Only when FDR abandoned his hostility toward the private sector in 1940, in preparation for wartime mobilization, did political uncertainty start to recede.

3. Violent Saviors, by William Easterly

William Easterly is a central figure in development economics and one of the fiercest critics of the arrogance behind many foreign-aid schemes. In The White Man’s Burden, he famously divided development thinkers into two groups: planners and searchers. Planners advance top-down, one-size-fits-all visions of progress and champion massive aid programs. Searchers pursue bottom-up solutions, relying on trial and error, local knowledge, and incentives that reward success and reveal failure.

Violent Saviors extends and deepens this critique. Easterly traces four centuries of Western interventions—from Puritan colonies to Africa, Asia, and 20th-century development bureaucracies—showing how coercion was repeatedly justified as benevolent “improvement.” The record is clear: these interventions failed, just as planners fail.

His central claim is that development without consent is not progress. Genuine progress arises through persuasion, voluntary cooperation, and market-driven discovery. Easterly contrasts the paternalism of interventionists with the liberal tradition of Adam Smith, for whom commerce was valuable precisely because it was voluntary. Violent Saviors is both economic history and moral defense of individual agency.

4. Two Paths to Prosperity, by Avner Greif, Joel Mokyr, and Guido Tabellini

Joel Mokyr, one of the 2025 Nobel laureates in Economics, is well known to readers for his sweeping histories of technological innovation. Here, alongside Avner Greif and Guido Tabellini, he tackles one of economic history’s most profound questions, what Kenneth Pomeranz called the Great Divergence: Why did Northwestern Europe surge ahead and surpass China?

The authors locate the answer in the forms of social organization that emerged around the year 1000. China grounded cooperation in extended kinship networks—stable structures, but tightly bound to family ties. Europe, by contrast, leveraged political fragmentation to build broader forms of cooperation among strangers: guilds, autonomous towns, monasteries, universities, and later, corporate firms.

These decentralized organizations enabled constraints on power, fostered scientific and intellectual experimentation, and eventually gave rise to rule of law, political representation, open science, and sustained innovation. China, more centralized and hierarchical, produced stability but not the same dynamism.

The book ultimately reminds us of the historical power of openness, decentralization, innovation, and peaceful cooperation among strangers.

5. The Thinking Machine, by Stephen Witt

Stephen Witt’s The Thinking Machine provides a narrative of how one company—Nvidia—accidentally became the engine of the AI revolution. Witt follows Jensen Huang’s decades-long bet on parallel computing, a gamble few believed in at the time and one that transformed a graphics-chip manufacturer into the firm whose hardware now trains the world’s most advanced models. The book shows how transformative breakthroughs emerge from individual initiative, competition, and the unpredictable logic of technological discovery. At a moment when many governments imagine they can steer or contain artificial intelligence, Witt’s story reminds us that world-changing progress rarely comes from central planning.

Across these five books runs a common thread: the importance of openness, the dangers of political overreach, and the transformative power of innovation and creative destruction. Together, they form a powerful case for free societies and the individuals who animate them.