The EU’s new plan to regulate speech, media, and elections.

The European Union has just unveiled the so-called European Democracy Shield. The name, while promising, claims to “protect” democracy on the basis of two pillars which, on principle, should raise concerns: combating “disinformation” and “foreign interference.”

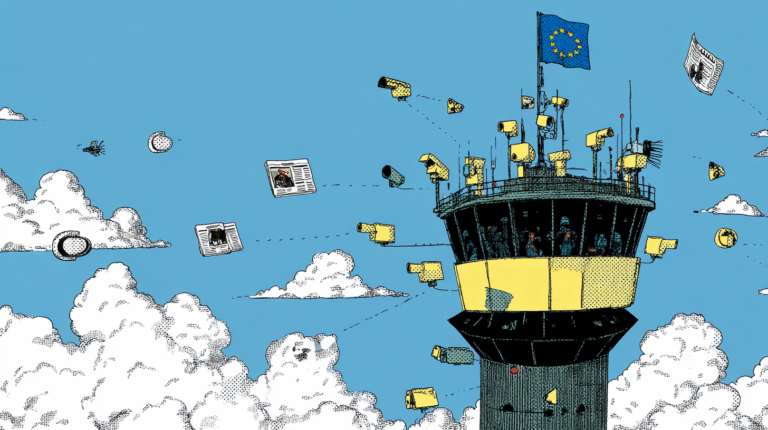

To that end, the EU will create a new European Centre for Democratic Resilience, intended to collect data from Member States on information manipulation; foreign information manipulation and interference (FIMI); and phenomena classified as disinformation. The same package also includes a European network of independent fact-checkers and a European Digital Media Observatory, which will be endowed with monitoring and analytical capacities during elections or moments of crisis.

Regarding free elections and the risk of foreign interference, the Commission additionally proposes to finance “independent journalism.” The irony that journalism financed by political institutions can never be genuinely independent seems lost on the Commission.

The European Democracy Shield is framed as an initiative to “reinforce” democracy at a time when the Union fears a rise in external hostilities. Yet, when examined closely, it reveals deeply troubling signs for the very democracy it claims to defend, beginning with the fact that it relies not on objective, legally defined threats, but on inherently subjective categories such as “disinformation,” “foreign interference,” or “information crises.” The subjectivity of these concepts allows such a wide margin of interpretation that it does not just risk turning into an instrument of political control; it seems almost designed as one.

The European Union is, after all, a supranational entity about which most Europeans do not feel fully informed, governed by a Commission that is not directly elected by the people. It therefore lacks the democratic, and moral, legitimacy to dictate how national democracies should function.

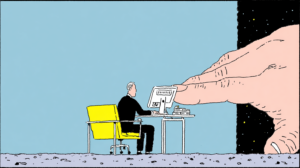

In recent years, the very notion of “disinformation” has become an ambiguous and expanding tool, enabling governments and institutions to establish an official narrative of what is acceptable, granting them moral authority to classify and remove opinions deemed “toxic” or “misleading.” This leads to an infantilization of the citizen, as if the simple act of thinking independently were somehow suspect.

Furthermore, the Shield allows the Commission to activate “joint response mechanisms” whenever it believes an “information crisis” exists. This is yet another undefined and vague concept, centralizing in the Commission the power to trigger exceptional measures, such as pressuring social media platforms, directing media outlets, and coordinating information campaigns. In practice, this functions as a form of permanent information emergency, without any effective democratic oversight.

By transforming fact-checkers into actors embedded within a European institutional structure, the Commission creates an authority to arbitrate political truth, a function incompatible with liberal democracy, which depends on the free clash of ideas and the plurality of interpretations.

Even the simple act of scrutinizing national elections in each Member State grants the Commission a power it should not possess, given the principle of subsidiarity, which states that the Union should intervene only when States are unable to act on their own. National elections are domestic matters and must remain so.

Allowing Brussels to exercise direct influence over electoral scrutiny opens the door to a dangerous scenario: the possibility of contesting or even invalidating national results under the pretext of “disinformation” or “foreign interference.” This risk is even more significant at a moment of rising Eurosceptic parties in several Member States, including those that are pillars of the Union itself.

In France, the Rassemblement National won 31.37% in the June 2024 European elections, the best result for any French party in 40 years. In Germany, the AfD obtained 20.8% in the 2025 federal elections and regularly appears above 25% in national polling.

These two countries are considered key Member States of the EU, not only because of their economic weight—together they account for around 40% of the EU’s GDP—but also because of the structuring political role they play in the European project. The so-called Franco–German engine often determines the direction of European integration.

If the European Commission gains the power to intervene in the scrutiny of national elections precisely in the countries that uphold the architecture of the EU, we would be facing an institutional precedent from which there is no return and one that could prove destabilizing for the Union as a whole.

To make matters worse, the creation of the Shield occurs in the same week that the Commission proposed a European intelligence unit, aimed at coordinating or aggregating information from national intelligence services. This coincidence suggests a concerted movement toward centralizing informational and security power in Brussels, without meaningful public debate.

European democracy does not need a “shield” to control speech, supervise elections, or finance the press. It needs informed citizens, truly free media, and institutions that respect the democratic sovereignty of each country, beginning with an internal reform of the European Union itself. The EU must become more transparent and, ironically, more democratic by granting greater decision-making power to the European Parliament, elected by Europeans, and reducing the power of the Commission, which lacks direct legitimacy.