John Stuart Mill’s ideas on education are not as well known as Milton Friedman’s. But they may deserve to be. Mill and Friedman agreed that government should not run schools, but for different reasons. (At least each emphasized different things.) Friedman was mainly concerned with productivity improvements that arise through competition. Mill was more concerned with freedom of thought. Mill valued the diversity of opinion that comes from people pursuing their own intellectual journeys, and all compulsion in opinion was anathema to him. The consequences of State schooling in America suggest Friedman and Mill were both correct.

School Productivity

State schools are a productivity disaster. In principle, public schools should thrive in the Information Age. Schools are in the information business, tasked with inculcating knowledge, and the processing and distribution of information have been vastly accelerated by interconnected computing technologies. Moreover, schools should benefit from the Flynn effect—the pattern cognitive psychologists have observed in which aggregate IQ rises a little bit each generation.

The State education system is centrally planned and run by committees, so choice and competition are lost from the system. Stagnation is therefore inevitable. Where market forces prevail, productivity improvement is normal. Computers and cell phones are vastly better than they were twenty years ago. Cars and planes less dramatically so, but they are safer, more fuel-efficient, and have new features. In the energy sector, hydraulic fracturing (fracking) has vastly increased the supply of fossil fuels, so that the United States

may become a net energy exporter within the next couple of decades. Less innovative sectors can still use technologies invented in other industries to raise productivity (e.g., by lowering their energy costs or improving their logistics) if competitive market forces are at work. But productive innovation is difficult and competition is the best school in which to learn it. State education plays hooky from that school, so it fails to learn.

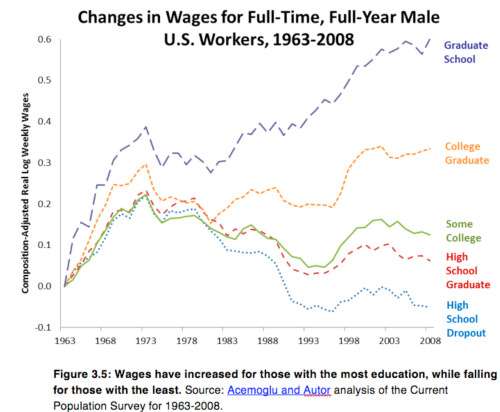

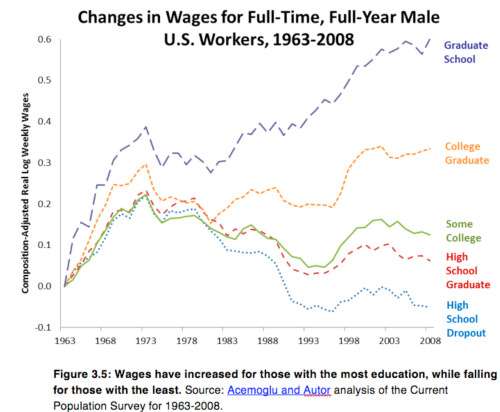

Poor public schools are a major bottleneck holding back the entire U.S. economy. The recent increase in inequality has been driven not by capital but by labor income, as

Saez and Piketty stress. This reflects sharply rising demand for certain kinds of skilled, educated workers, combined with little supply response. The public schools and universities are unable and/or unwilling to train the kinds of people the market wants. Eric Brynjolffson argues in his book

Race Against the Machine that workers are unable to keep up with new technology. Brynjolffson illustrates his point with the chart shown below:

The fact that wages of high school graduates have fallen is a painful remark about how much the market values what the public schools produce. In spite of these high labor premiums, college completion rates among men

have actually fallen. College is overregulated and oversubsidized, and there is too much power in the hands of accreditation agencies answerable to the Department of Education. But there is still far more competition and choice there than at the K–12 level. Thanks to competition, the U.S. university system is generally regarded as the best in the world and as

an important source of U.S. economic competitiveness. Of course, the top universities—Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Stanford, etc.—are private. And the consensus in academia is that universities would be equipped to produce many more bright college graduates if the public schools provided more students with basic skills.

Milton Friedman wanted to make K–12 education more like the university system through vouchers. Under a voucher system, financing K–12 education would still be the government’s job, but running K–12 education would be opened up to competition and largely privatized. Each student’s family would get a certain dollar value’s worth of vouchers, which could only be spent on education. “Government” schools would get their money by collecting the vouchers of students who chose to attend them and converting those to cash through the government. Direct financing of public schools through the government budget would be curtailed or eliminated. Meanwhile, vouchers could also be used to pay for private school tuition.

Today, the Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice seeks to “advance Milton and Rose Friedman’s vision of school choice for all children.” Voucher programs have been adopted in several countries, including free-market Chile and social-democratic Sweden. In the United States, there has been progress in overcoming legal challenges to school vouchers (especially

Zelman v. Simmons-Harris), and voucher programs have been adopted in cities like Cleveland and Milwaukee and states like Indiana. Where tried,

vouchers have improved educational outcomes, just as economic theory says they should.

J. S. Mill on the State Curriculum Mill

There are underlying philosophical reasons to oppose State schooling as well. In the magnificent On Liberty, John Stuart Mill is at his best when he defends freedom of thought. It forms the basis of his opposition to State-run schooling, though he saw plenty of room for the State in supporting education. It’s a crucial distinction. He actually took an unusually statist position for the time in calling for compulsory education:

Consider, for example, the case of education. Is it not almost a self-evident axiom, that the State should require and compel the education, up to a certain standard, of every human being who is born its citizen? Yet who is there that is not afraid to recognize and assert this truth? . . . While this is unanimously declared to be the father's duty, scarcely anybody, in this country, will bear to hear of obliging him to perform it. Instead of his being required to make any exertion or sacrifice for securing education to the child, it is left to his choice to accept it or not when it is provided gratis! It still remains unrecognized, that to bring a child into existence without a fair prospect of being able, not only to provide food for its body, but instruction and training for its mind, is a moral crime, both against the unfortunate offspring and against society; and that if the parent does not fulfill this obligation, the State ought to see it fulfilled, at the charge, as far as possible, of the parent.

Mill also thought that financing education was primarily the parent’s responsibility (not the taxpayer’s) and that the State should force parents to pay if necessary; he also believed the State should finance needy children’s education.

Mill was very insistent, however, that the State must get out of the business of running schools:

Were the duty of enforcing universal education once admitted, there would be an end to the difficulties about what the State should teach, and how it should teach, which now convert the subject into a mere battle-field for sects and parties, causing the time and labor which should have been spent in educating, to be wasted in quarrelling about education. If the government would make up its mind to require for every child a good education, it might save itself the trouble of providing one. It might leave to parents to obtain the education where and how they pleased, and content itself with helping to pay the school fees of the poorer classes of children, and defraying the entire school expenses of those who have no one else to pay for them.

For Mill, a major reason not to have State-run schools is that they inevitably give the government too big a role in deciding what children should be taught, and thus in shaping public opinion, culture, and belief. Critics of vouchers often make the exact opposite argument—namely, that public schools impose a welcome uniformity, which vouchers would disrupt. The Anti-Defamation League makes the following

argument against vouchers:

As our country becomes increasingly diverse, the public school system stands out as an institution that unifies Americans. Under voucher programs, our educational system—and our country—would become even more Balkanized than it already is.

But it is not good for Americans to be unified in their opinions except to the extent that their opinions are true. And the best path to truth is not to impose uniformity, but to let a free marketplace of ideas flourish. That is what Mill understood, and expressed as lucidly, fairly, and persuasively as anyone ever has.

I cannot do justice to Mill's erudition, or his unrivaled knowledge of intellectual history. Stripped to its barest essentials, Mill argues that we shouldn’t suppress unpopular or minority views because they might, after all, be true. He also argues that even if the majority view is true, our understanding of it will remain poor and impotent if we don’t hear the criticisms that can be made of it and how they are to be answered.

Even when something true comes to be universally believed, it’s still important to keep its criticisms alive, even if artificially. Doing so allows for an appreciation of the truth as compared to the various alternatives, whether they’re fallacies or simply empirically untrue. Hence Plato writing his philosophy in dialogues so that the views he rejected could get a hearing, and readers would see how truth differed from, and bested, all manner of false alternative opinions (or sometimes, why certain opinions were clearly false even if the truth were not known). Again, the scholastic philosophers of the Middle Ages liked to structure their writings in the form of objections and answers to the objections, so that truth could stand out by contrast with error.

Since error must get a hearing for truth to be properly understood, it is foolish to silence the real, live dissenter. On the contrary, we should thank him for giving us a chance to clarify the truth by answering him. Strikingly, Mill goes beyond demanding mere legal freedom of speech and holds that public opinion, too, ought not to impose conformity of views, but should give full respect to all manner of honest differences and disagreements.

It is from these premises that Mill raises “objections . . . not . . . to the enforcement of education by the State”:

That the whole or any large part of the education of the people should be in State hands, I go as far as any one in deprecating. All that has been said of the importance of individuality of character, and diversity in opinions and modes of conduct, involves, as of the same unspeakable importance, diversity of education. A general State education is a mere contrivance for moulding people to be exactly like one another: and as the mould in which it casts them is that which pleases the predominant power in the government, whether this be a monarch, a priesthood, an aristocracy, or the majority of the existing generation, in proportion as it is efficient and successful, it establishes a despotism over the mind, leading by natural tendency to one over the body.

The one exception to this principle, paradoxically, underscores it:

When society in general is in so backward a state that it could not or would not provide for itself any proper institutions of education, unless the government undertook the task; then, indeed, the government may, as the less of two great evils, take upon itself the business of schools and universities, as it may that of joint-stock companies, when private enterprise, in a shape fitted for undertaking great works of industry does not exist in the country.

In other words, State-run education is only fit for savages—and only as a temporary measure.

Mill does not think, however, that the State needs to police children to make sure they have their butts in classroom seats for x number of hours per year. The State need not concern itself with inputs, but rather, with whether adequate learning is taking place, as ascertained in public examinations. That is wise, indeed wonderfully prescient. It is a vision fit for the age of online education, when no school could compete with what the Internet has to offer to a disciplined and motivated student. Mill characterizes the content of the exams from the same objection to State control of opinion:

To prevent the State from exercising through these arrangements, an improper influence over opinion, the knowledge required for passing an examination . . . should, even in the higher class of examinations, be confined to facts and positive science exclusively. The examinations on religion, politics, or other disputed topics, should not turn on the truth or falsehood of opinions, but on the matter of fact that such and such an opinion is held, on such grounds, by such authors, or schools, or churches . . . All attempts by the State to bias the conclusions of its citizens on disputed subjects, are evil; but it may very properly offer to ascertain and certify that a person possesses the knowledge requisite to make his conclusions, on any given subject, worth attending to. A student of philosophy would be the better for being able to stand an examination both in Locke and in Kant, whichever of the two he takes up with, or even if with neither: and there is no reasonable objection to examining an atheist in the evidences of Christianity, provided he is not required to profess a belief in them.

It is ironic that contemporary America prides itself on being a bastion of freedom of thought, yet it would hardly occur to the typical American to have such scruples about safeguarding the life of the mind from the shadow of State power.

Mill might have supported a system of standardized tests like that established in the No Child Left Behind Act, but with this difference: He would have left it to individuals to decide for themselves how to acquire the knowledge to pass those tests, with the government intervening only when learning failed to take place. Mill would also have opposed state financing for the education of non-poor children, but given how entrenched that has become, an easy step in Mill’s direction might be to let students who pass standardized tests leave school and receive the money that would have been spent on them, or most of it, in an educational savings account that could be partly spent on books and tutors, but mostly saved for college.

It’s probably not the ideal solution, but it would liberate a lot of students from schools that mostly waste their time. The market—educational entrepreneurs—would find lots of ways to serve their learning needs better than central school boards ever will. The growing availability of such options, in turn, would create pressure to loosen the public schools’ stranglehold on education. And it would engender a diversity of intellectual strengths so that we would have much to learn from each other throughout our lives.