These early heroes deserve considerable credit.

(Editor’s Note: Portions of this essay are drawn from Mr. Reed’s forthcoming book, Born of Ideas: How Principles, Faith, and Courage Forged America, to be released in April 2026 by Faith & Freedom Press, the publishing house of Grove City College in Pennsylvania.)

Out of a total population of 2.5 million at the time of the Declaration of Independence, black Americans numbered about half a million, or 20%. Most were enslaved, but at least 30,000 were free men and women.

Slavery is always and everywhere an unconscionable stain, an egregious error, a monstrous outrage, a horrible sin. Every human possesses a natural right to be his own master, so long as he does not deny that same right to others.

Most people take that principle for granted today, but it wasn’t the governing rule anywhere for most of world history. Only a small percentage of all the people who have lived on this planet were truly free; most were either outright slaves or they were serfs or subjects who lived in constant fear of tyrants. For thousands of years, freedom was the exception, if it existed at all. It is mostly a recent development of the last two or three centuries.

The world progressed from acceptance and ubiquity of chattel slavery in the 18th century to near-universal abolition in the 19th. That is one of the most remarkable transformations in history. The spirit of the Declaration of Independence and the sacrifices of millions of people of all colors helped mightily to accomplish that metamorphosis. America is not exceptional because we had slavery, but rather, because of the lengths to which we ultimately went to get rid of it.

Whether free or slave, did black Americans play a role in the fight for liberty during the American Revolutionary era? Yes indeed, they did. It’s a story that didn’t earn much attention in history books until recent decades. When I was in school in the 1950s and 1960s, I think I heard of just one of them, Crispus Attucks, a black sailor who was the first person killed by British soldiers in the March 1770 Boston Massacre.

Black people were to be found among both patriots and loyalists, depending in large part on which side seemed more likely to advance their prospects for freedom. Joining up with the British was as much a toss of the dice as embracing the American cause, for Britain at the time was the largest slave-trading nation on the globe. London wouldn’t abolish the transatlantic slave trade until 1807, and it didn’t free slaves within all of its colonies until 1834.

Slavery in the northeastern American Colonies, on the other hand, was already dying out. Vermont (not one of the original thirteen) abolished slavery and even granted black Vermonters the right to vote as early as 1777. After the last of it in America was extinguished at the end of the Civil War in 1865, slavery persisted in major parts of the rest of the world.

Black patriots distinguished themselves on behalf of the American cause in ways that deserve remembering. In The Black Regiment of the American Revolution (2004), for instance, Linda Crotta Brennan told the story of an all-black regiment that ranked among the finest military units of the war. It protected a sizable contingent of Washington’s army by trouncing three fierce assaults by Hessian mercenaries in the Battle of Rhode Island.

Born into slavery in Massachusetts, Peter Salem fought courageously at the Battle of Bunker Hill, even killing a top British officer in the fight. A Virginia slave, James Armistead, proved to be one of the most effective spies for the patriot cause, delivering crucial information to the Marquis de Lafayette.

Military historian and retired Lt. Col. Michael Lee Lanning’s 2021 book, African Americans in the Revolutionary War, revealed that both free and enslaved blacks served on the patriot side in every major battle on land and at sea. Thirteen black soldiers even served in the newly formed US Marine Corps. Lanning found that

White volunteers for state militias and the Continental army joined for periods of three to twelve months. Most spent an average of six months in the military and then returned to their civilian occupations. On the other hand, many Black men enlisted “for the duration” in exchange for their freedom. The average length of time in service for African Americans during the Revolution was four and a half years—eight times longer than the average period for white soldiers.

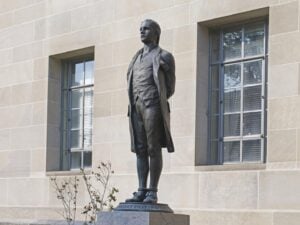

The black heroes who helped the American side were not all men. One of the notable African American women was Phillis Wheatley, whose weapon was neither a sword nor a gun but a pen. Born in 1753, she became a writer, the first black woman to publish a book of poetry.

Brought from West Africa to America at the age of seven, she was purchased by the Wheatley family of Boston, who named her Phillis after the ship on which she arrived. She was an extraordinarily precocious young girl. She quickly learned to read and write and exhibited a special fondness for poetry. Amazed at her talent, the Wheatleys encouraged her.

When she was only fifteen, Phillis wrote a poem in praise of King George III, but it was for his support of the repeal of the hated Stamp Act. She hinted at her growing sentiments for freedom:

May George, beloved by all the nations round,

Live with heav’ns choicest constant blessings crown’d!

Great God, direct, and guard him from on high,

And from his head let ev’ry evil fly!

And may each clime with equal gladness see

A monarch’s smile can set his subjects free!

Freedom was again a subject of another Wheatley poem a year later. Titled “To the Rt. Hon William, Earl of Dartmouth,” it read as follows:

Should you, my lord, while you peruse my song,

Wonder from whence my love of Freedom sprung,

Whence flow these wishes for the common good,

By feelings hearts alone best understood,

I, young in life, by seeming cruel fate

Was snatch’d from Afric’s fancy’d happy seat:

What pangs excruciating must molest,

What sorrows labour in my parents’ breasts.

Steel’d was that soul and by no misery mov’d

That from a father seiz’d his babe belov’d

Such, such my case.

And can I then but pray

Others may never feel tyrannic sway?

At the age of 20, Wheatley’s first book of poems was published in London. It earned her fame on both sides of the Atlantic, which led to her emancipation just eighteen months before the fight with Britain began at Lexington. She became, writes historian Henry Louis Gates, “the most famous African on the face of the earth, the Oprah Winfrey of her time.”

No less a luminary than General George Washington latched on to her work. He praised it and even arranged for the publication of one of her poems in the Virginia Gazette in March 1776. In a letter to her a month earlier, the general said, “the style and manner [of your poetry] exhibit a striking proof of your great poetical talents.” He invited her to visit him, which she did that same month just days before the British evacuated Boston. Gates reports that Washington spent a half-hour in conversation with her as fighting raged nearby.

As a pioneering African American poetess, Phillis Wheatley (along with other black heroes of the Revolution) fostered new thinking in America about black people. They could write, they could fight, they could yearn for freedom just as passionately as people of any other color. It would take too long, of course, for minds to change sufficiently to fulfill the Declaration’s promise by emancipation for all, but these early heroes deserve considerable credit for making it possible.

Additional Resources:

African Americans in the Revolutionary War by Michael L. Lanning

Complete Writings by Phillis Wheatley

Letter from Washington to Wheatley

Mister Jefferson and the Trials of Phillis Wheatley by Henry Louis Gates

The Black Regiment of the American Revolution by Linda Crotta Brennan

Seven Black Heroes of the Revolution by Colette Coleman

The Trials of Phillis Wheatley: America’s First Black Poet and Her Encounters with the Founding Fathers by Henry Louis Gates

A Voice of Her Own: The Story of Phillis Wheatley by Kathryn Lasky

Five Things They Don’t Tell You About Slavery by Rich Lowry

Recognizing Hard Truths About America’s History with Slavery by Lawrence W. Reed

The History of Slavery You Probably Weren’t Taught in School by Lawrence W. Reed