Let’s see what AI ends up being used for before spelling out what damages will get what penalties.

It’s not news to anyone that European governments love to over-regulate. But last year, worried about emerging AI technology, European lawmakers took their regulatory habit even further. In an act of economic self-sabotage, they implemented a “regulate first, innovate later” approach to AI.

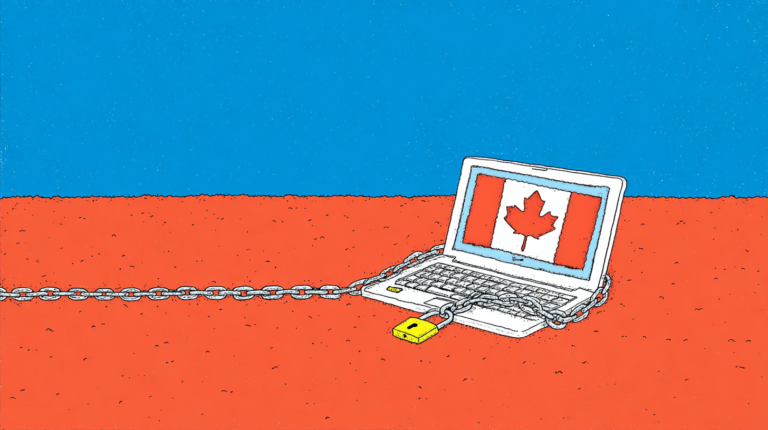

Instead of waiting for technological innovations to emerge and then responding with appropriate regulation, the European Commission decided it would be the first major regulatory body to pre-empt the innovation and regulate it right away, sight unseen. If it weren’t so misguided, this self-parody would be laughable. In any case, it’s an approach Canada needs to avoid.

The idea behind the new EU rules was to impose obligations on AI companies based on their products’ presumed risk factors. But risk factors related to rights are very hard to assess in advance and costing them before any discernible damage has occurred is a complex process most companies are not in a position to undertake, if it can be done at all.

At this early stage in the AI revolution, it’s hard enough to predict the uses to which AI tools will be put, let alone the damage, if any, they may inflict. Yet the EU law stipulates that firms deemed “high-risk” under the proposed rules can be fined €15 million or up to 3% of their global revenues, whichever is higher.

Though much AI regulation is motivated by animus against supposedly marauding tech giants, its effect, like that of most regulation, is to benefit precisely these large firms. Companies like OpenAI, Google and Meta can bear the burden and cost of regulation much better than startups. The same is true of most large companies across all sectors.

And who gets the short end of the stick? Consumers. That’s the true effect of excessive regulation. Consumers benefit most from increased competition, since it leads to better products and lower prices. But by erecting costly compliance obligations, regulators all but guarantee only a few of the biggest entities can survive.

Europe’s AI regulation is similar to its General Data Protection Regulation, which was instituted to try to protect personal data collection. Research shows it favoured large platforms, which were better able to absorb the cost of these regulations, and that overall competition was reduced as a result. The regime has strengthened the market share of large digital companies and brought a slowdown in innovation in the sector in Europe compared to the United States.

In AI, meanwhile, private investment has grown rapidly in the United States while stagnating in Europe. In 2024, more than US$29 billion was invested in the US, nearly 20 times the US$1.5 billion invested in Europe. And 1,143 AI companies were created in the US, nearly three times the number created in Europe (447). The number of AI applications available in the EU has fallen by a third, and the rate of entry of new applications by 47.2%. It would not be shocking if history repeated itself under a similarly tightly regulated Canadian AI regime, were we to adopt one.

AI gains are slated to be felt across the economy. Some researchers estimate that AI could raise the productivity of unskilled workers by as much as 14%. Productivity and standards of living are closely correlated. The more productive workers are, the more profit they generate and the higher their possible negotiated wage.

Canadian productivity has basically stagnated for a decade. If we follow Europe’s lead and over-regulate AI, we risk pre-emptively restricting significant economic gains for Canadians. Europe hitting the brakes on innovation has likely reduced its global competitiveness—based on zero proof that any of the proposed protections were fit for purpose.

Despite our new-found post-Trump affinity for Europe, Canada should not make the same mistake as the EU.

This article has been reprinted with permission from the Montreal Economic Institute.