At last, the Mugwumps have their modern-day champion: Professor David Tucker, a historian at the University of Memphis. The Mugwumps are best known as civil service reformers who worked within the Republican party to quash the spoils system with the Pendleton Act of 1883. As Tucker shows, however, the Mugwumps were much more than mere moral reformers. They were eloquent and persuasive spokesmen for free markets and free trade throughout the late 1800s.

The Mugwump name came from the Algonquian word for “chief.” Tucker looks at, among others, the careers of Mugwump “chiefs” William Graham Sumner, professor at Yale University; E. L. Godkin, editor of The Nation; Carl Schurz, senator from Missouri; David Wells, a government statistician; and Henry Adams, popular writer descended from two presidents.

The Mugwumps greatly admired the writings of British thinkers Adam Smith, Richard Cobden, and John Stuart Mill. The ideas of free markets, strong property rights, sound currency, and limited government were hallmarks of Mugwump thinking. As Tucker notes, “They mastered historical and statistical material that demonstrated that steam and electricity had multiplied the productivity of workers and would create an abundance if only individuals learned personal virtue and if governments withdrew their market interferences.”

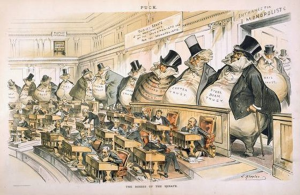

Not only would society function more smoothly if entrepreneurs were unleashed and government restrained, but poor people and immigrants would have greater chances for success. Protective tariffs, according to Mugwump research, helped fewer than 10 percent of American workers and pushed prices upward for the rest. Tariffs further created lobbies of special interests who corrupted government by pressuring politicians to vote special favors for them.

The Mugwumps deplored the political arena and preferred to write rather than run for office. Their big political success was when they bolted the Republican party in 1884 and helped Grover Cleveland win the presidency. Cleveland proved to be a strong free-market thinker and his two terms were the high point of Mugwump influence.

In the late 1800s, the Mugwumps were challenged by the Populists, who wanted government aid for farmers; silver miners, who wanted the government to buy large amounts of silver at high prices; and some intellectuals, who saw government as a useful tool to create a more perfect society. Tucker describes these challenges to free-market ideas and observes that Mugwumps opposed federal tinkering because “government policies violated liberal beliefs in absolute individual rights of life, liberty, and property.”

Tucker does an excellent job of presenting the Mugwumps and their ideas, which he says were compelling and logical. They won some battles, lost others, and, by the early 1900s, were overshadowed by the Progressives. “Politicians,” Tucker says, “always needed encouragement to do the right thing, and even if the advice was rarely followed, critics were not necessarily failures.”

In the past, historians have ridiculed Mugwumps as priggish, selfish, and suffering from declining status in society. Tucker argues that this view says more about the historians than it does about the Mugwumps. “Mugwumps were given their reputation for failure by later cheerleaders for the welfare state,” he observes. “[A]fter the Great Depression of the 1930s turned educated opinion to Keynesian economics, nineteenth-century liberals who feared government as the enemy of freedom and progress were recast as selfish, wrongheaded agents for the middle class.”

Tucker’s research is solid and he explores a wealth of primary and secondary sources. His writing is clear and crisp and his chapters are well organized. Most historians assume that free-market ideas lost because they were not sound; Tucker, by contrast, assumes that the Mugwumps held ideas that were solid and enduring. To explain their ultimate defeat, he explores how the German ideas of statism and empire-building began to permeate American society in the late 1800s.

Tucker’s book is an excellent addition to the literature on the Gilded Age and a valuable correction to the standard books by historians Richard Hofstadter, Ari Hoogenboom, and John Sproat.